12 April 2024: Clinical Research

Quality of Life of Chronic Heart Failure Patients During and After COVID-19: Observational Study Using EuroQoL-Visual Analogue Scales

Emoke Ilona Sukosd1ABD, Nilima Rajpal KundnaniDOI: 10.12659/MSM.943301

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e943301

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Chronic diseases affect both the mental and physical health of patients. An acute infection can further deteriorate it. The multi-organ damage and acute respiratory distress caused by coronavirus leads to worsening of the previously stable state of chronic diseases.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: The aim of our study was to compare the quality of life during pre-acute-post-COVID-19 infection status of chronic heart failure (CHF) patients based on responses on the EuroQoL-visual analogue scales (EQ VAS). Patients suffering from CHF and a COVID-19 infection were included in our study. EuroQoL questionnaires responses were recorded at 3 time-points (Q1 before COVID-19 infection, Q2 during an acute episode of COVID-19, and Q3 at 6 months after COVID infection). The statistical analysis was carried out both in a cross-sectional view for each time-point and longitudinally. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for independent series was applied in the case of subgroup comparison, and the Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used in the longitudinal study.

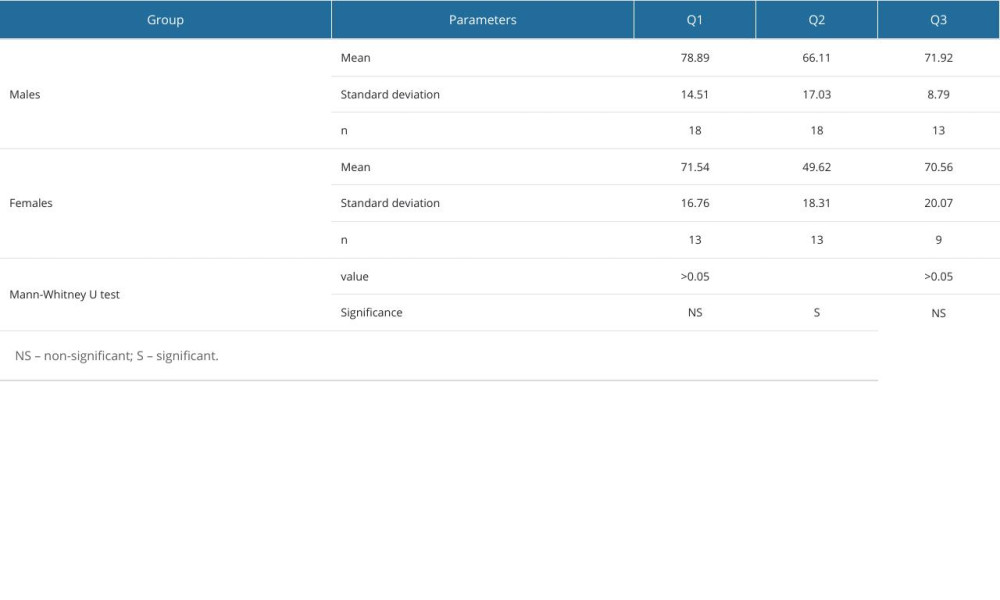

RESULTS: Based on the responses given by the patients, there was decline in QoL noted in all patients, mainly in females, included in our study during the acute phase of the infection, as compared to their pre-COVID-19 admission for a follow-up for their heart disease (Q1: 78.89 vs Q2: 66.11 in males and Q1: 71.54 vs Q2: 49.6 in females, p=0.015 for Q2). Improvement was noted in the evaluation done after 6 months to the acute episode, although the values failed to attain to that of the initial pre-COVID-19 analysis, with Q3: 71.92 in males and 70.56 in females.

CONCLUSIONS: Understanding these implications can guide healthcare interventions for better management and support, particularly in the context of pre-existing chronic conditions exacerbated by acute infections like COVID-19. The results may prompt further research into the long-term effects of COVID-19 on individuals with chronic diseases, guiding future studies to explore specific interventions or preventive measures. QoL during the acute phase of COVID-19 infection is affected on a larger extent as compared to previous analysis in chronic heart failure patients. Larger studies with a longer time span can indicate the time duration required for CHF patients to attain the pre-COVID-19 QoL status. Developing methods to increase the accuracy of QoL evaluation can further reduce the bias witnessed, especially in previously unhealthy subjects. The study’s findings could inform healthcare providers about the heightened risk and specific challenges faced by chronic heart failure patients during and after a COVID-19 infection. Policymakers can use these findings to develop targeted public health policies aimed at protecting and supporting individuals with chronic conditions during and after infectious outbreaks, ensuring comprehensive healthcare strategies.

Keywords: COVID-19, Heart Failure, Quality of Life

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus greatly affected quality of life in all age groups. Patients with comorbidities were highly affected, and healthy people were also badly affected. Several studies have been performed to evaluate the impact of lockdowns imposed to restrict the spread of the virus, which led to serious mental health disorders around the world [1–5]. Healthcare systems were fighting both the COVID-19-related health issues like acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi-organ involvement, and the psychological issues seen as early and late complications of COVID-19 infection. As the mortality rates grew, the panic that spread during the lockdown phase was difficult to handle by psychologists working worldwide, both in hospital settings and providing online consultation sessions. Healthcare workers were also confronted by this unprecedented situation and were witnessing extreme psychological distress [6–8].

The patients suffering from chronic diseases or non-communicable diseases (NCD) showed rapid deterioration of their condition when infected with COVID-19 [9–11]. In fact, quality of life (QoL) is already compromised in NCD patients and a COVID-19 viral infection can further worsen it both from the physical and mental health point of view, further worsening the already compromised quality of life. Chronic heart failure patients, due to their restricted life style and health uncertainty, often face depression and anxiety [12]. Evaluating the influence of COVID-19 infection on the quality of life among individuals with chronic heart failure is crucial. Such an assessment holds significance as it provides insights that can direct healthcare interventions, enhancing the overall management and support for these patients. This is especially pertinent in addressing the unique challenges posed by acute infections like COVID-19 on individuals with pre-existing chronic conditions. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of these implications becomes essential for tailoring effective and targeted healthcare strategies. Various studies have evaluated the QoL in heart failure patients of different severity grades and effects of interventions such as daily exercise and counselling [13,14]. Similarly, COVID-19 affected the QoL of patients during the acute episode and later during post-acute COVID-19 and long COVID-19, where the clinical findings still persist during the first 4 weeks or for a period beyond 4 weeks after the viral replication ceases, creating complications [15,16].

EQ-5D-5L analysis is a descriptive system comprising 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has 5 levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. The patients are asked to indicate their current health state by ticking the box next to the most appropriate statement in each of the 5 dimensions. This decision results in a 1-digit number that expresses the level selected for that dimension. The digits for the 5 dimensions can be combined into a 5-digit number that describes the patient’s health state [17].

The EuroQoL-visual analogue scales (EQ VAS), records the patient’s self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale, where the endpoints are labelled ‘The best health you can imagine’ and ‘The worst health you can imagine.’ The VAS can be used as a quantitative measure of health outcome that reflect the patient’s own judgement [17].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of a COVID-19 infection on the QoL of chronic heart failure patients during the acute phase of the infection (during their hospital stay) and at 6 months after the acute episode and to compare it with the pre-COVID phase QoL.

Material and Methods

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The collected data allowed us to analyze the data from 2 perspectives:

Normality of data distribution was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test [18], which showed a departure from normality for all 3 series. Consequently, for comparison we used the Wilcoxon signed rank test [19]. Moreover, as some patients died in the interval between Q2 and Q3 and as the Wilcoxon signed rank is a paired test, for the comparisons the corresponding case were discarded and the W-statistic was considered for interpreting the significance of the differences (as we had n>20) and z-value for P [19].

Microsoft Excel spreadsheets were used for storing the data and for basic statistical processing for tables, charts, descriptive statistics, and ANOVA.

STATEMENT OF ETHICS AND PATIENT CONSENT:

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes,” Timisoara (approval number: 15/2019).

Formal written informed consent was obtained from all the patients on admission as a part of routine procedure, as being a university-affiliated hospital, their data can be used for future academic and research purposes, keeping their personal identity information confidential.

Results

Results are presented in 2 sections: comparison between subgroups for each time-point and the longitudinal view.

Three types of a subgroup were analyzed: age-related, gender-related, and survivors/deceased.

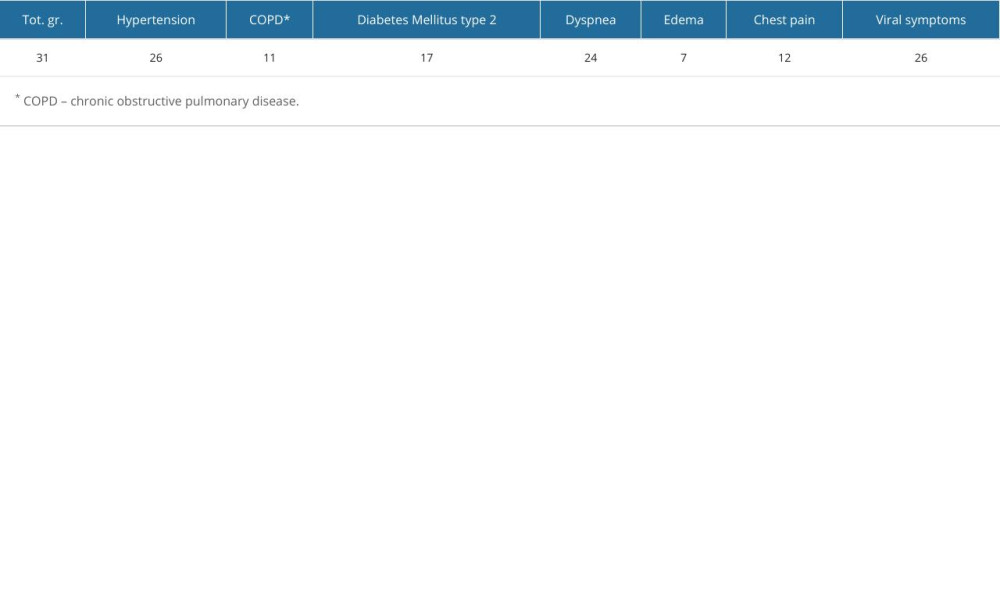

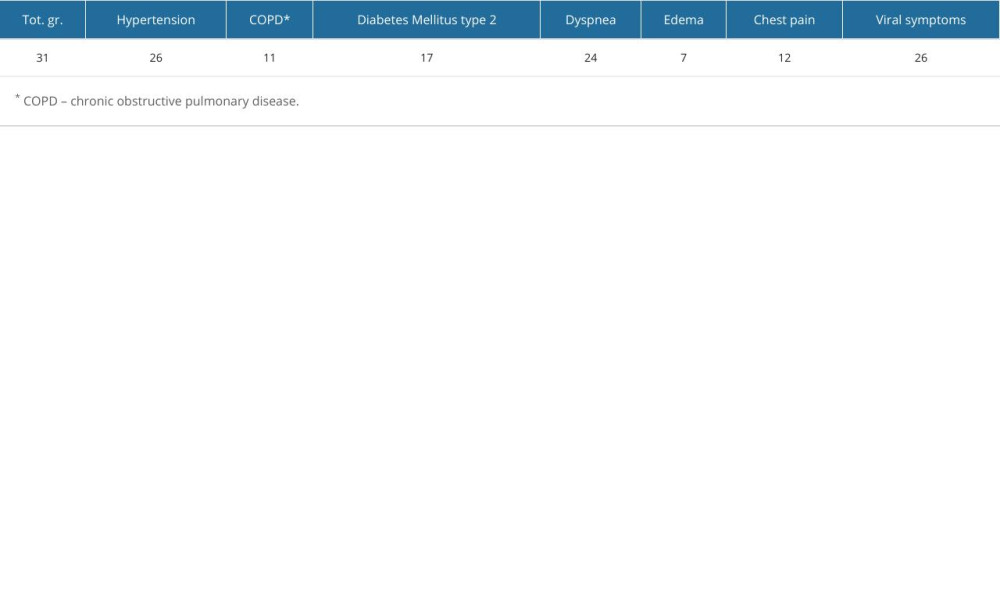

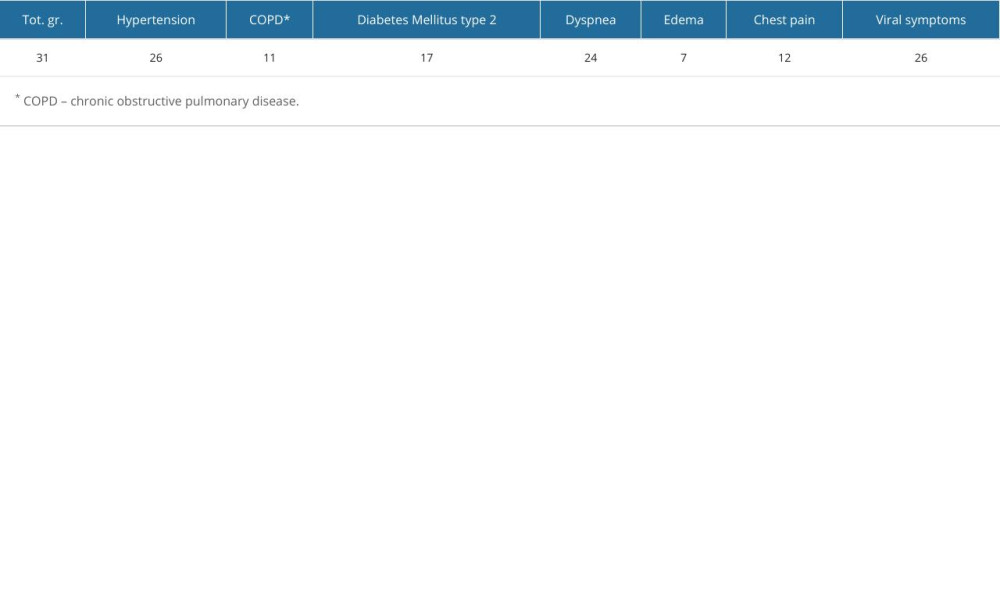

Table 1 shows the various types of comorbidities.

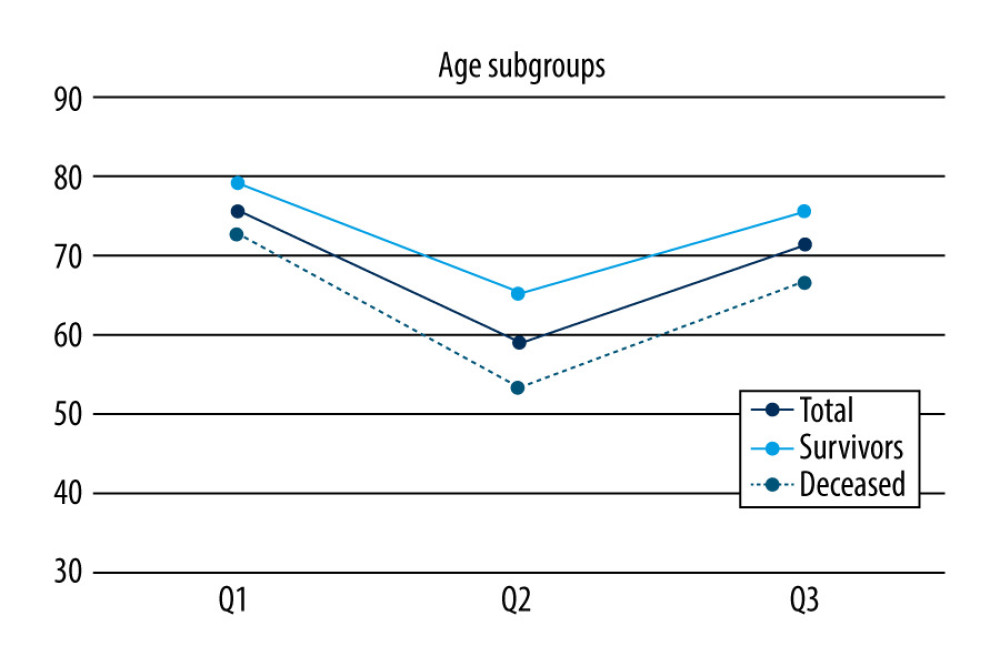

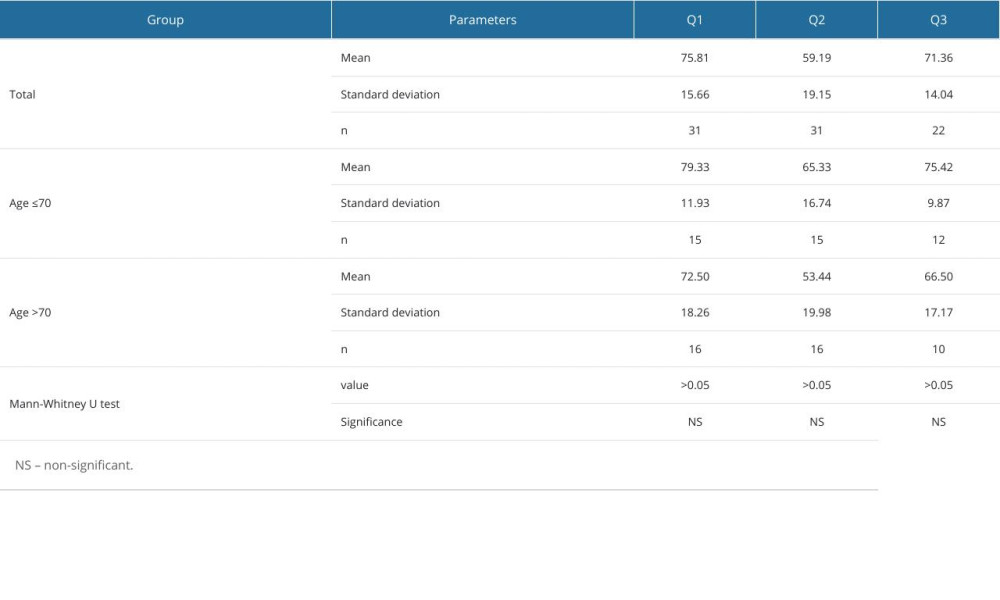

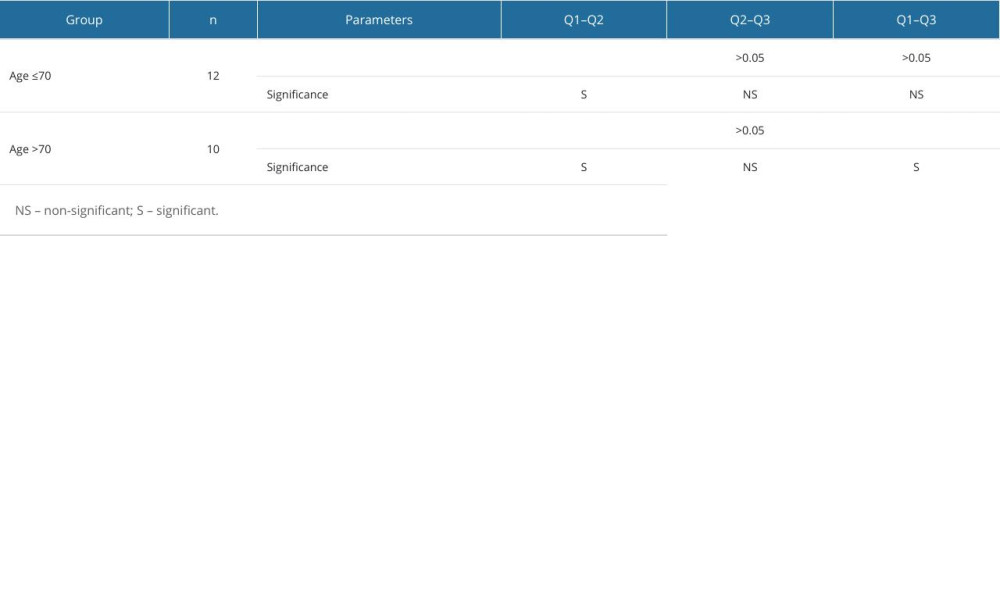

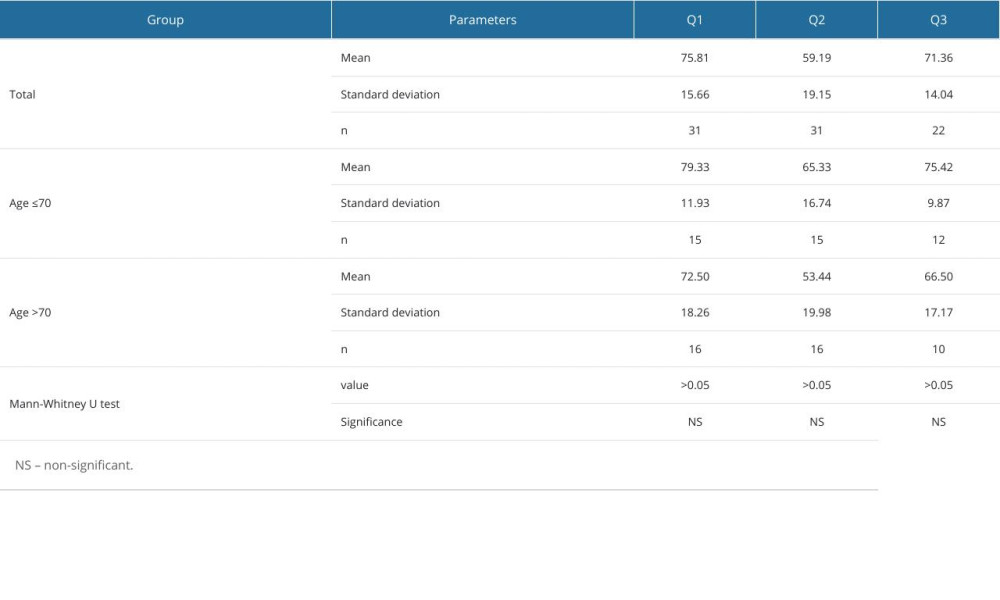

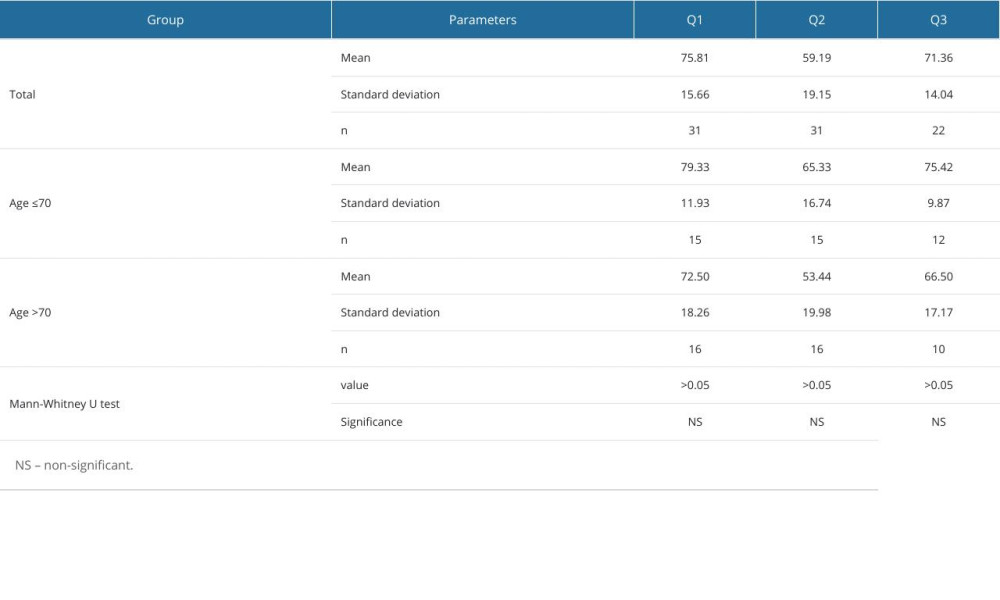

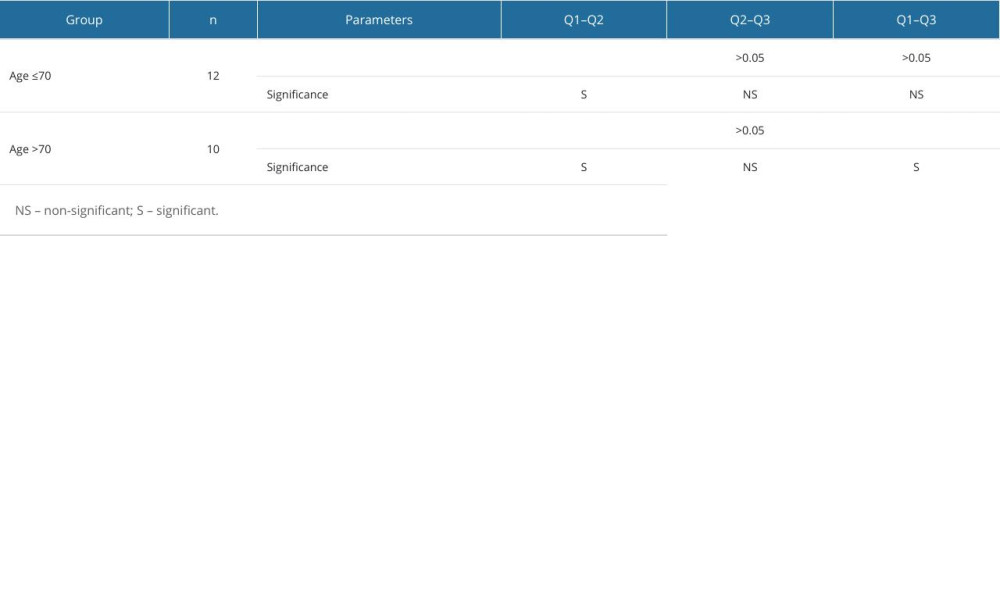

Advanced age had a less relevant influence in the group studied by us. Thus, the patients were divided into 2 groups, one aged >70 year and the other ≤70 years. It was found that pre-covid elderly patients had a lower quality of life than those over 70 (Q1=72.50 compared to Q1=79.33), without there being a significant statistical difference between the 2 groups (

In the acute phase of COVID-19, the condition of patients deteriorates, especially in the elderly (Q2=53.44 compared to Q2=65.33), without there being a significant difference between the 2 groups (

At the 6-month evaluation, the condition improved in both groups, maintaining the previous trend (older patients have a more impaired quality of life), Q3 in patients over 70 years old was 66.50, compared to Q3 in those under 70 years old, where it is 75.42, without a significant difference between the groups (

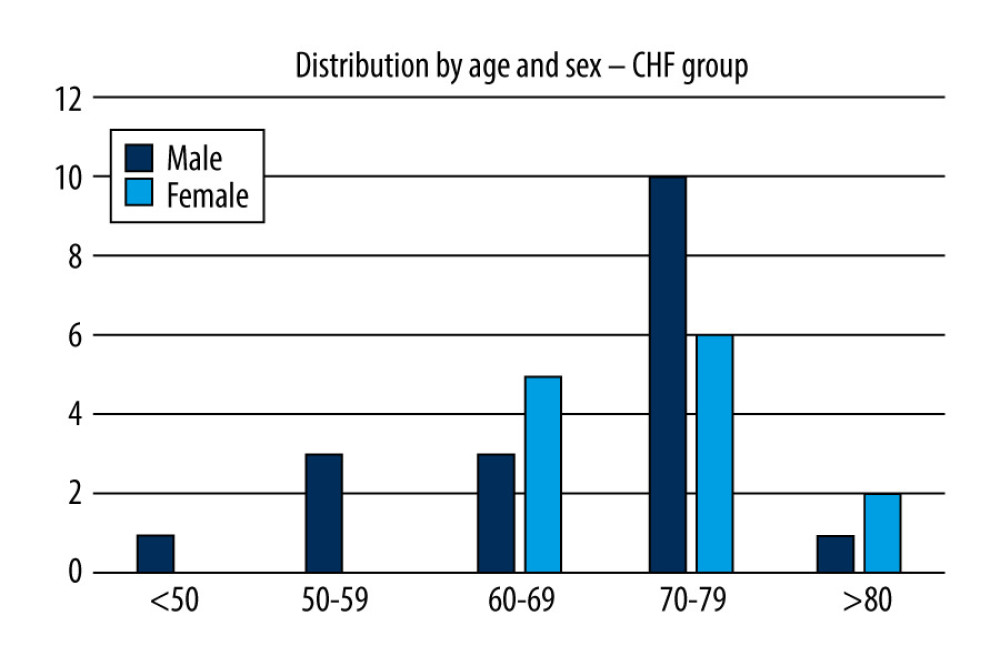

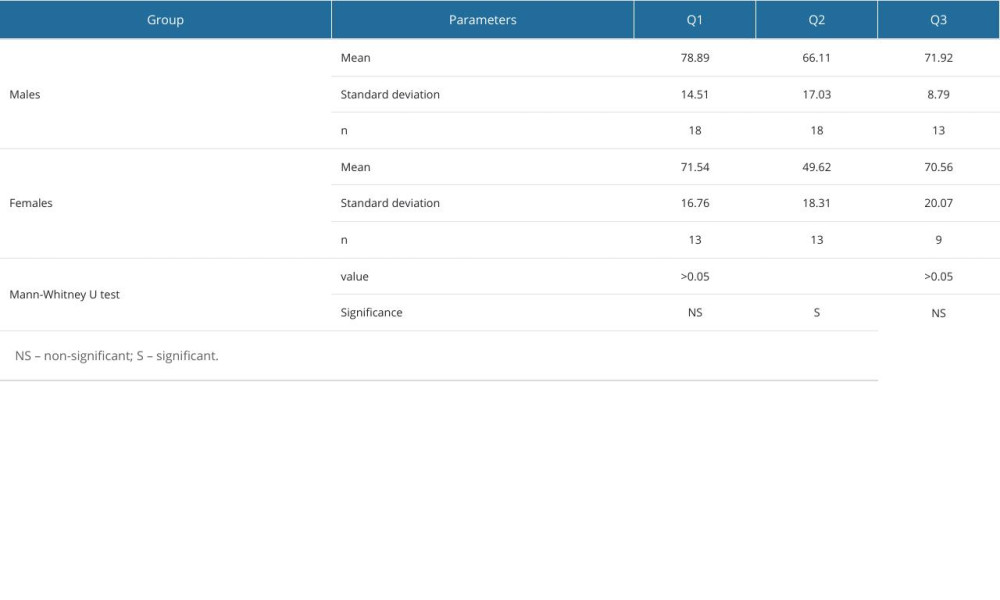

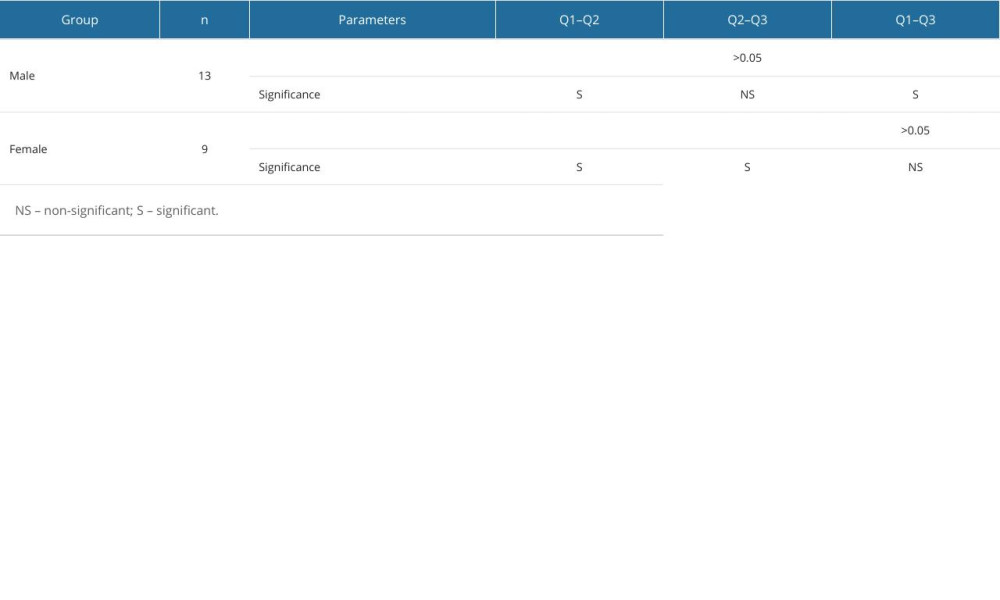

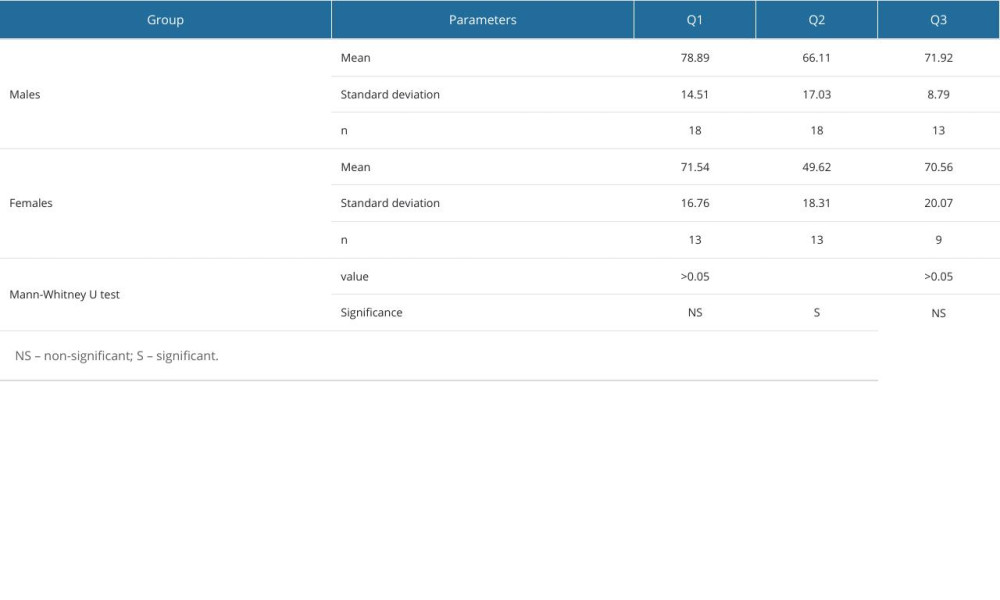

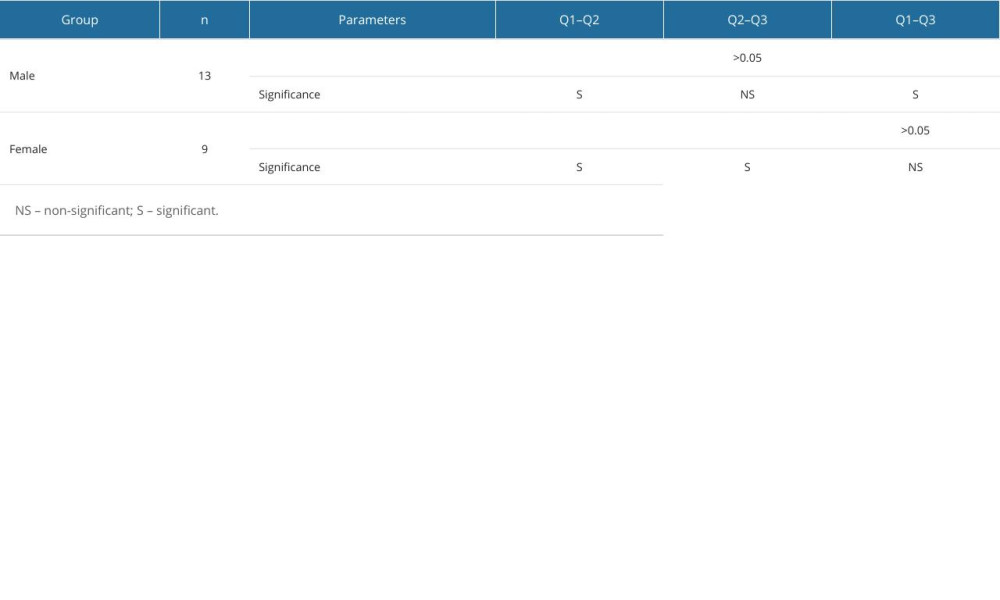

The studied group contained 42% women and 58% men.

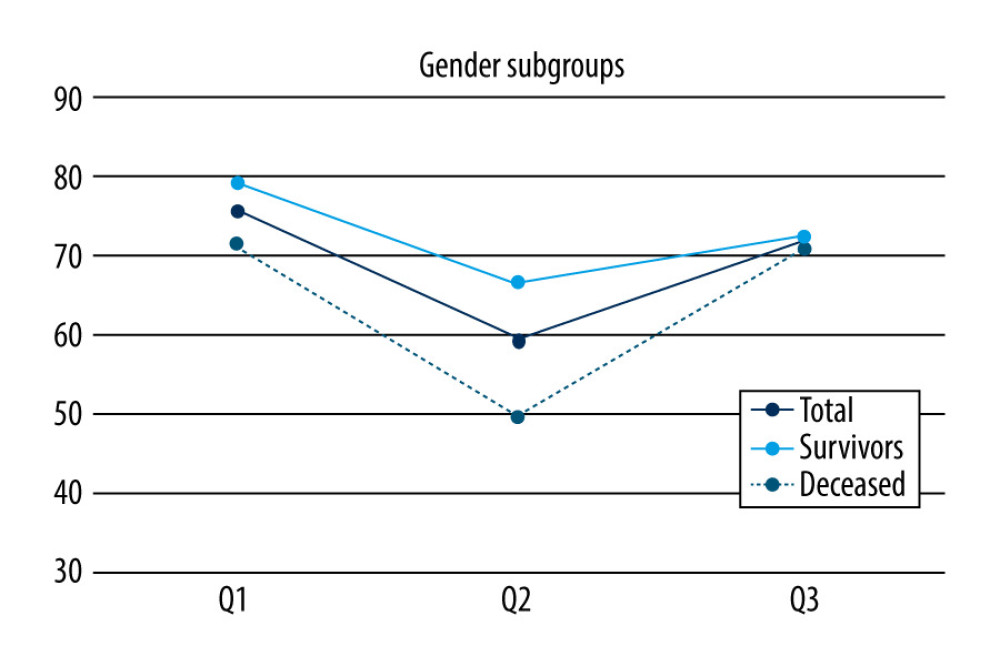

At Q1, female patients with heart failure (Q1 average of 71.54) had a lower quality of life than men with heart failure (Q1 average of 78.89), but without a significant statistical difference between the groups (

In the acute phase of COVID-19, there was a more pronounced deterioration in quality of life in women than in men (Q2=49.62 vs Q2=66.11) (

After the acute phase of COVID-19 had passed, at 6-month follow-up, an improvement in the quality of life was found in both sexes (Q3 females=70.56 compared to Q3 males=71.92), without a statistically significant difference between the sexes (

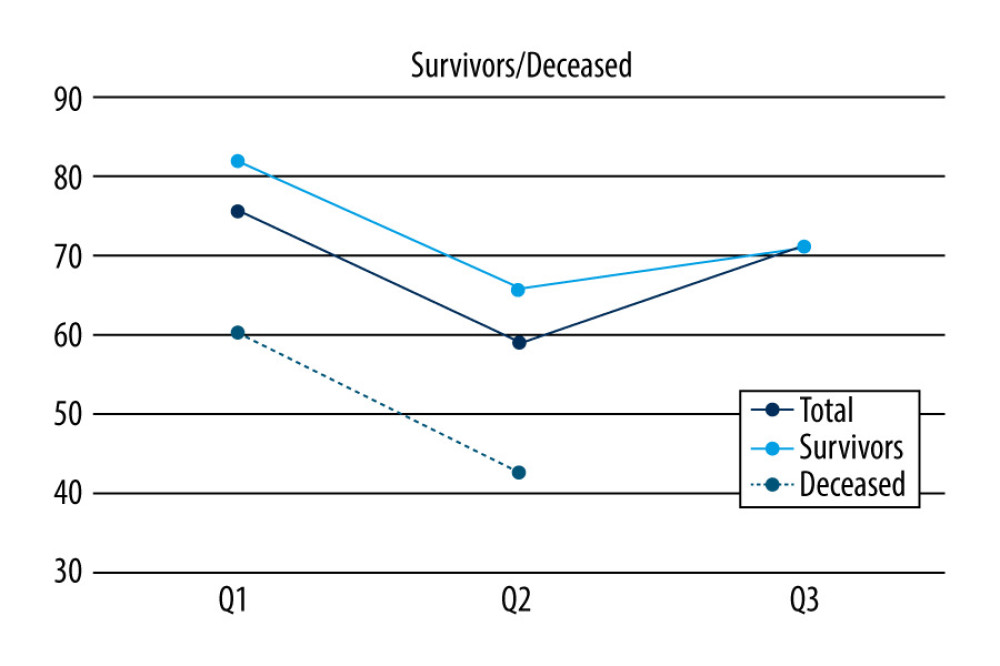

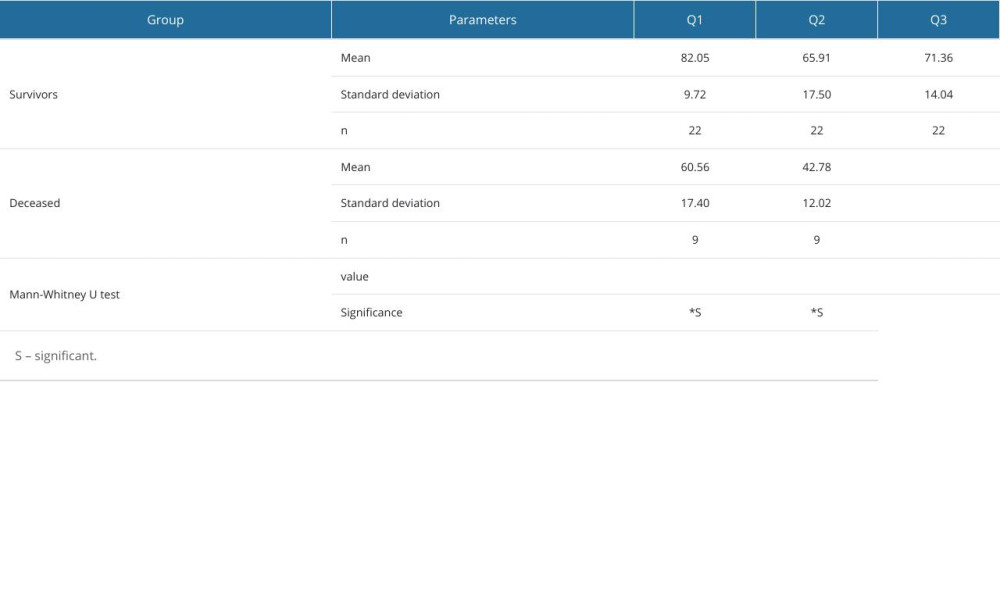

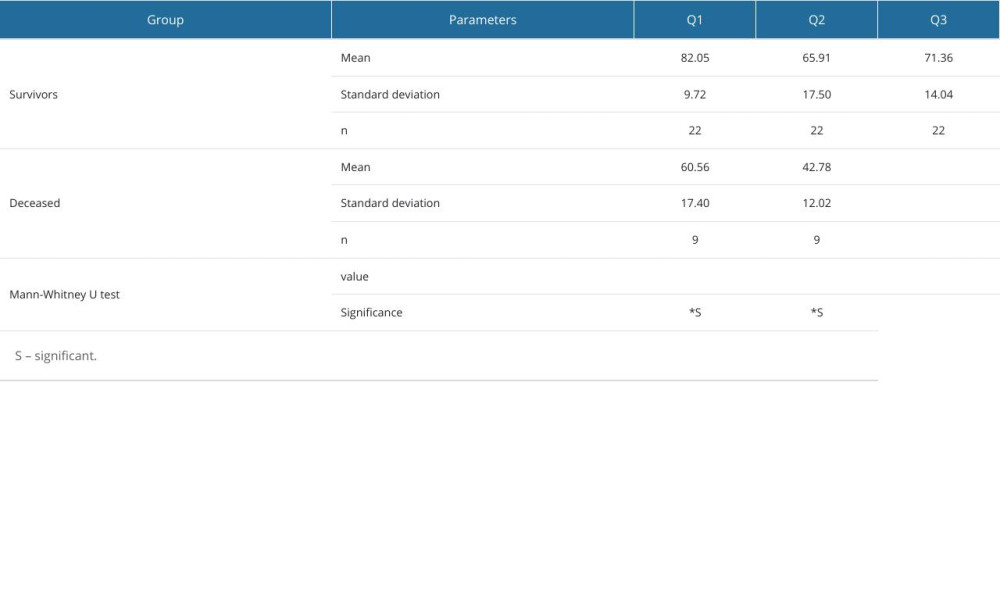

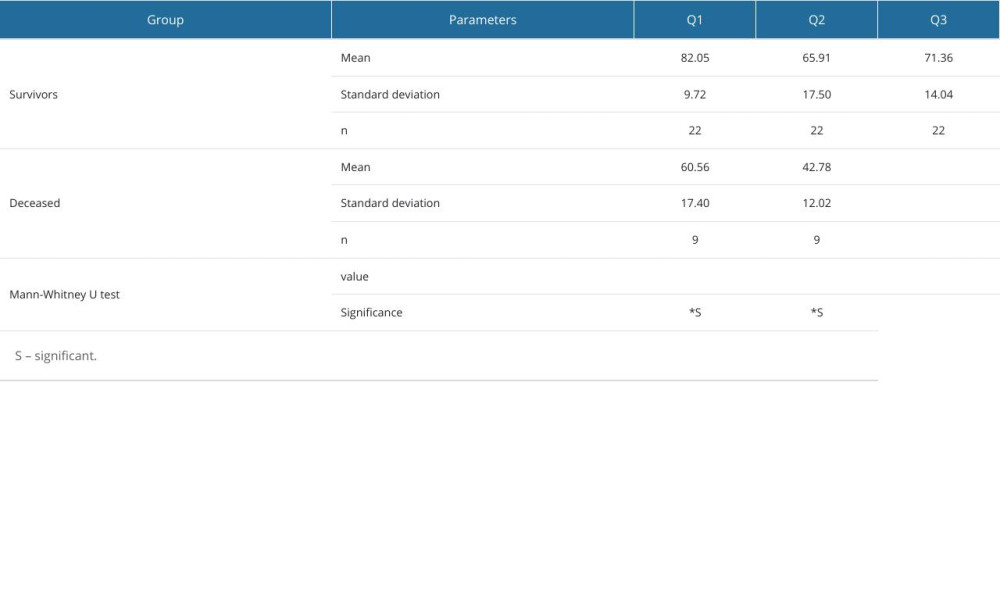

The acute phase of COVID-19 led to a significant (

For comparing QoL values at different time-points, a paired test is recommended and as the Shapiro-Wilk test showed departure from normality, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied.

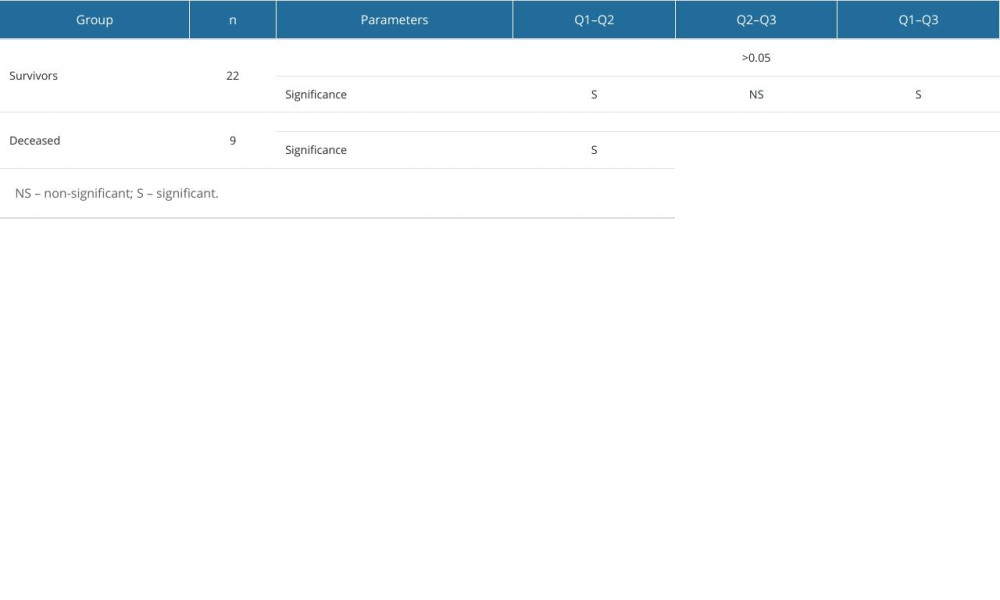

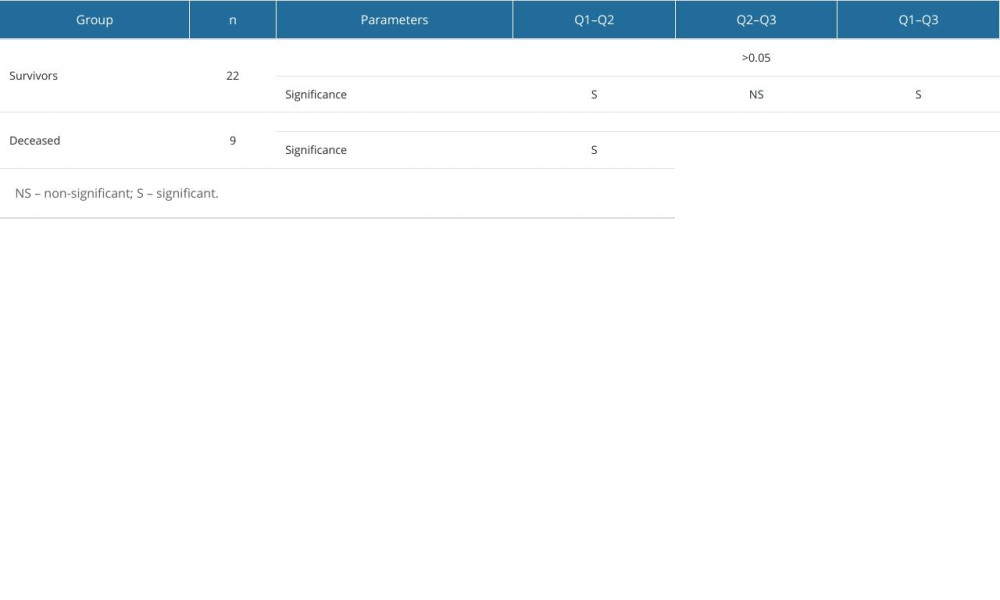

The decrease in QoL from the pre-COVID-19 state to the acute COVID-19 state was significant (

For the Q1–Q2 interval, the test could also be applied to the subgroup of deceased, resulting in a significant decrease in the acute phase of the disease.

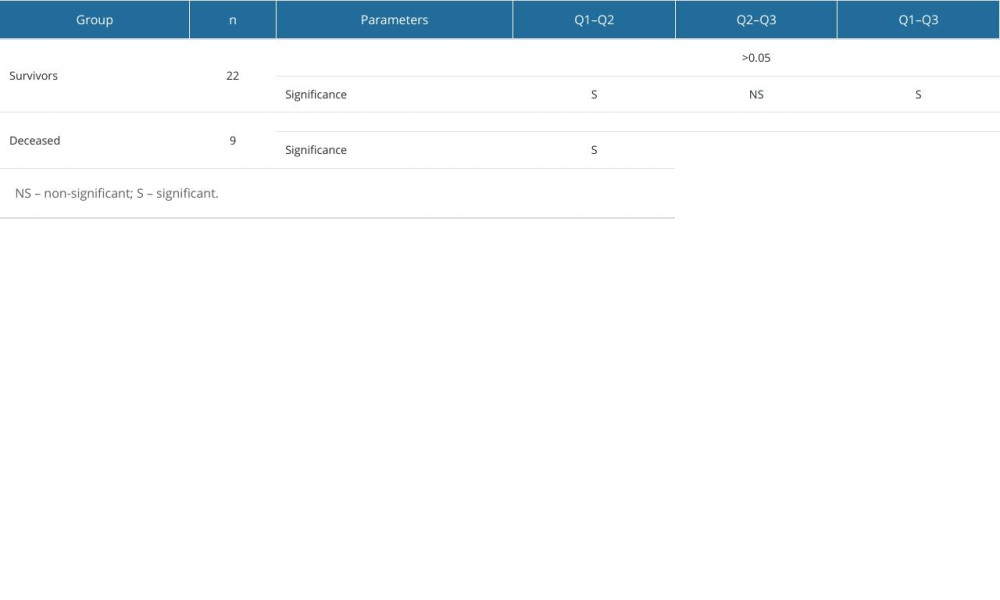

The values in Q1 and Q2 for the deceased had to be removed, and a total sample remained with 22 patients. The QoL evolution is presented in Figure 2.

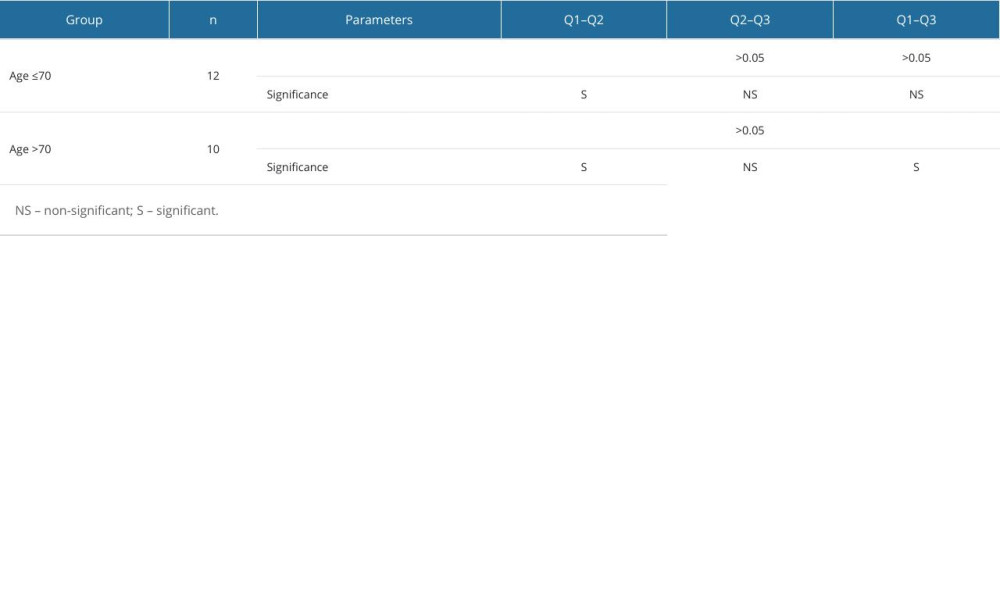

We could also follow the evolution of QoL in survivors for sex-related and age-related subgroups.

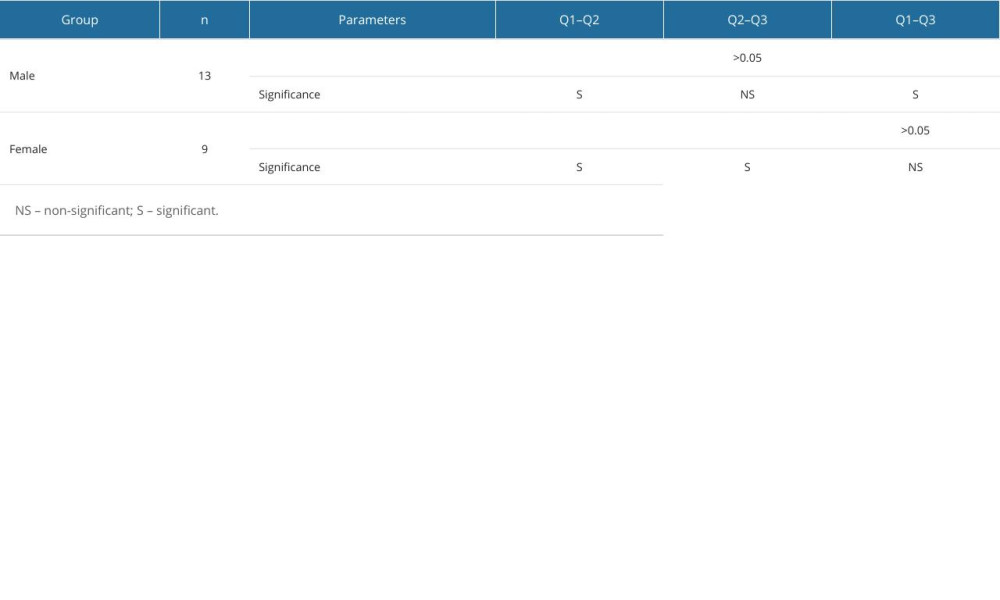

However, the recovery after COVID was different for the 2 groups. For males, the difference between Q2 and Q3 was not significant and the final QoL in Q3 remained significantly lower than the initial QoL in Q1. For females, the Q2–Q3 recovery was significant and the final state was close to the initial state (Q1), with no significant Q1–Q3 differences (Table 7).

Discussion

Changes in QoL can serve as early indicators of disease progression or complications in HF patients. Tracking QoL over time allows healthcare providers to monitor the effectiveness of treatment and identify patients who may be at increased risk of worsening HF or other adverse outcomes.

The significant results from our study and a significant body of evidence emerging from studies conducted over the past 3 years points to the detrimental impact of COVID-19 on various aspects of quality of life (QoL). The impact is multifaceted and can affect both physical and mental well-being.

The presence of multiple comorbidities can significantly diminish a person’s quality of life by affecting physical health, mental well-being, social interactions, and financial stability. Addressing comorbidities comprehensively through coordinated care and support services is crucial for improving the quality of life for patients with multiple health conditions.

Older adults over 70 years of age are particularly vulnerable to experiencing worse quality of life during acute COVID-19 compared to younger individuals, primarily due to increased risk of severe illness, higher mortality rates, social isolation, barriers to healthcare access, and psychological distress. Efforts to mitigate these effects should include targeted interventions to address the unique needs of older adults, such as ensuring access to healthcare, providing social support, and promoting mental well-being [23].

Older adults are more likely to experience frailty, which can further compromise their ability to recover fully from illness and return to their previous level of functioning. They may experience higher levels of anxiety or fear related to COVID-19 due to their increased vulnerability to severe illness and mortality, which can negatively affect their quality of life even after recovery.

The observed gender difference in QoL during the acute phase of COVID-19 and subsequent recovery could be influenced by a combination of biological, sociocultural, psychological, and healthcare-related factors. Females may initially experience higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression during the acute phase of COVID-19 due to concerns about their health and the health of their families. However, with time and effective coping strategies, they may be able to adapt and recover, leading to improvements in QoL [24].

The observed association between a worse QoL before COVID-19 and increased mortality within the first 6 months of follow-up may reflect underlying health vulnerabilities, limited functional capacity, psychological distress, socioeconomic disparities, and immune dysregulation that predispose individuals to adverse outcomes during and after COVID-19. Identifying and addressing these pre-existing factors could be crucial for improving outcomes and reducing mortality risk in vulnerable populations affected by COVID-19 [25].

In a study conducted by Méndez et al, the short-term effects from neuro-psychiatric viewpoint and QoL of COVID-19 patients were evaluated using standardized questionnaires to assess the mental and physical components of QoL, as well as the presence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress syndrome. These questionnaires have well-established psychometric properties and are widely used in research on QoL. In almost half of the patients, a low QoL was noted for both the mental and physical components. Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress syndrome were found to be present in about one-fourth of COVID-19 survivors [18]. The study had a large sample size and a well-defined sample population. However, the study did not control for pre-existing conditions or other factors that could have influenced the results, and it was conducted in a single geographic location, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. While in our study the impact on QoL was much worse because our patients had a pre-existing condition, so their QoL was already compromised and COVID-19 worsened it further. Since a patient’s state of mind when filling out the questionnaire can drastically influence responses, there is a need for methods to factor in the influence of state of mind to improve the accuracy of responses.

Tabacof et al [19] employed standardized questionnaires to evaluate the physical and cognitive functioning and quality of life in patients who had recently recovered from COVID-19, showing decreased physical and cognitive functioning, as well as reduced quality of life after COVID-19 in previously normal individuals. Nevertheless, the research failed to account for pre-existing conditions, which might have impacted the outcomes. We specifically concentrated on a selected group of individuals who had recently recovered from COVID-19. The results of our study, where the patients included had chronic heart failure, show that COVID-19 worsened their already-compromised QoL.

The anxiety and depression during lockdown as the virus spread rapidly round the world and deaths were being reported round the clock had a major psychological impact on the responses of patients in the acute COVID-19 phase.

A strength of our study is that our results can be applied to other populations of chronically ill patients with heart failure, particularly those who have COVID-19. Our findings suggest that COVID-19 can have a significant impact on the quality of life (QoL) of these patients, and that this impact can persist even after the acute phase of the disease has resolved.

Regarding generalizability of our results, it is important to note that the study’s findings may be relevant to policymakers and healthcare providers who are developing strategies for managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 on patients with chronic illness. For example, the study highlights the need for comprehensive care plans that address both the medical and psychosocial needs of these patients.

Overall, the results of this study provide valuable insights into the impact of COVID-19 on the QoL of chronically ill patients with heart failure. However, more research is needed to confirm these findings and to understand the long-term implications of these findings for patient care and public health policy, mostly because the study had a relatively small sample size and was conducted in a single geographic location.

Our study has certain limitations. Surveys based on questionnaires are very subjective. Daily life events can also create bias, especially in chronically ill patients. Telephone conversations were conducted if a participant could not attend a follow-up appointment, which may have reduced the accuracy of results due to being less alert during a phone call than in person, but attention level could not be judged over the phone.

Conclusions

The study highlights the significant impact that chronic illnesses such as heart disease can have on both physical and psychological well-being. This underscores the need for comprehensive healthcare plans that address not only the medical needs of these patients but also their emotional and psychological well-being. Chronic cardiac diseases can cause great psychological stress on patients and their families, and a pandemic situation like COVID-19 can further worsen the physical and mental well-being of these compromised patients. Uncertainty regarding the disease’s evolution further justifies the responses of questionnaires asking how would you rate your current state of health, when asked in such scenarios. Ways to overcome the bias can further improve the accuracy of such studies where external factors have a major influence on patient responses. Larger studies with longer follow-up periods can help understand the time span required for regaining the pre-COVID-19 level of QoL, as in our study the 6-month results were improved but to previous levels.

Understanding how COVID-19 affects the QoL of HF patients can lead to development of more effective interventions and care strategies. By identifying the factors that contribute to QoL decline, healthcare providers can tailor treatment plans to address these specific needs and improve the overall well-being of HF patients.

By prioritizing patient well-being, healthcare providers can create a supportive environment that fosters adherence to treatment, promotes healthy lifestyle habits, and encourages social engagement, all of which contribute to better QoL and overall health outcomes.

Tables

Table 1. Comorbidities presented in the studied group. Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups.

Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups. Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups.

Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups. Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups.

Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups. Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups.

Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups. Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups.

Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups. Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups.

Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups.

References

1. Flanagan EW, Beyl RA, Fearnbach SN, The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults: Obesity (Silver Spring), 2021; 29(2); 438-45

2. Adams LM, Gell NM, Hoffman EV, Impact of COVID-19 ‘stay home, stay healthy’ orders on function among older adults participating in a community-based, behavioral intervention study: J Aging Health, 2021; 33(7–8); 458-68

3. Teixeira MT, Vitorino RS, da Silva JH, Eating habits of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of social isolation: J Hum Nutr Diet, 2021; 34(4); 670-78

4. Sharma M, Aggarwal S, Madaan P, Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Sleep Med, 2021; 84; 259-67

5. Burkart S, Parker H, Weaver RG, Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on elementary schoolers’ physical activity, sleep, screen time and diet: A quasi-experimental interrupted time series study: Pediatr Obes, 2022; 17(1); e12846

6. Danet Danet A, Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Western frontline healthcare professionals. A systematic review: Med Clin (Barc), 2021; 156(9); 449-58

7. Labrague LJ, Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies: J Nurs Manag, 2021; 29(7); 1893-905

8. Raudenská J, Steinerová V, Javůrková A, Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol, 2020; 34(3); 553-60

9. Hernández-Galdamez DR, González-Block M, Romo-Dueñas DK, Increased risk of hospitalization and death in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing noncommunicable diseases and modifiable risk factors in Mexico: Arch Med Res, 2020; 51(7); 683-89

10. Chang AY, Cullen MR, Harrington RA, Barry M, The impact of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on noncommunicable disease patients and health systems: A review: J Intern Med, 2021; 289(4); 450-62

11. Dessie ZG, Zewotir T, Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients: BMC Infect Dis, 2021; 21(1); 855

12. Bordoni B, Marelli F, Morabito B, Sacconi B, Depression and anxiety in patients with chronic heart failure: Future Cardiol, 2018; 14(2); 115-19

13. Zhuang C, Luo X, Wang Q, The effect of exercise training and physiotherapy on diastolic function, exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis: Kardiol Pol, 2021; 79(10); 1107-15

14. Mizukawa M, Moriyama M, Yamamoto H, Nurse-led collaborative management using telemonitoring improves quality of life and prevention of rehospitalization in patients with heart failure: Int Heart J, 2019; 60(6); 1293-302

15. Liu K, Zhang W, Yang Y, Respiratory rehabilitation in elderly patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled study: Complement Ther Clin Pract, 2020; 39; 101166

16. Chippa V, Aleem A, Anjum F, Post acute coronavirus (COVID-19) syndrome: StatPearls, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), Copyright©, StatPearls Publishing LLC

17. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/

18. Méndez R, Balanzá-Martínez V, Luperdi SC, Short-term neuropsychiatric outcomes and quality of life in COVID-19 survivors: J Intern Med, 2021; 290(3); 621-31

19. Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Wood J, Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and participation: Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 2022; 101(1); 48-52

Figures

Tables

Table 1. Comorbidities presented in the studied group.

Table 1. Comorbidities presented in the studied group. Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups.

Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups. Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups.

Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups. Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups.

Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups. Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups.

Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups. Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups.

Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups. Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups.

Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups. Table 1. Comorbidities presented in the studied group.

Table 1. Comorbidities presented in the studied group. Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups.

Table 2. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between age-related subgroups. Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups.

Table 3. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between gender-related subgroups. Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups.

Table 4. Statistical characteristics at the 3 time-points and Mann-Whitney U test between survivors and deceased subgroups. Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups.

Table 5. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of survivors/deceased subgroups. Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups.

Table 6. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of age-related subgroups. Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups.

Table 7. Wilcoxon signed rank test for longitudinal view of gender-related subgroups. In Press

08 Mar 2024 : Laboratory Research

Evaluation of Retentive Strength of 50 Endodontically-Treated Single-Rooted Mandibular Second Premolars Res...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.944110

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Effects of Sugammadex and Neostigmine on Postoperative Neuromuscular Blockade Recovery in Pat...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942773

12 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparing Neuromuscular Blockade Measurement Between Upper Arm (TOF Cuff®) and Eyelid (TOF Scan®) Using Miv...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943630

11 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhancement of Frozen-Thawed Human Sperm Quality with Zinc as a Cryoprotective AdditiveMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942946

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952