26 July 2022: Clinical Research

Emergency Removal of Ingested Foreign Bodies in 586 Adults at a Single Hospital in China According to the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Recommendations: A 10-Year Retrospective Study

Qing Liu1ABCD, Fei Liu2BCD, Huahong Xie1ABCD, Jiaqiang Dong1BCDF, Hui Chen1ACEF*, Liping Yao1AEFGDOI: 10.12659/MSM.936463

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e936463

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines recommend that ingested foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract are removed as an emergency within 6 hours, with an endoscopic approach that is individualized according to the type of foreign body identified. This retrospective study evaluated the 10-year experience of a single hospital in China performing emergency removal of ingested foreign bodies in 586 adults.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: Between 2011 and 2020, medical records of 642 adults with a diagnosis of foreign bodies ingestion were retrospectively screened. The timing of endoscopic intervention was classified according to ESGE recommendations. Uni- and multivariate analyses were performed.

RESULTS: We included 586 patients. The median (range) diameter of foreign bodies was 2.5 (1-24) cm: for sharp ones it was 2.5 (1.5-4.0) cm and for long ones it was 16.9 (10-24) cm. The most common site of foreign body lodgment was the esophagus (n=481; 82.1%); 45.6% (n=252) received emergent removal within 6 hours, while 32.2% (n=178) underwent urgent removal within 24 hours. There were 583 (99.5%) foreign bodies removed successfully and the complication rate was 17.9%. Major complications occurred in 45 patients (7.7%). Female sex and non-emergent endoscopy after 6 hours were significantly associated with a higher overall complications rate. For major complications, older age, time interval >24 hours, and sharper objects were associated with major complications.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings from this retrospective study support the ESGE statement that endoscopic removal of ingested foreign bodies from the upper GI tract within 6 hours reduces complication rates for adults in the emergency setting.

Keywords: Emergency Medical Services, Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal, Esophageal Perforation, Intraoperative Complications, Adult, China, Female, Foreign Bodies, Hospitals, Humans

Background

Foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract are common problems in clinical practice worldwide [1,2]. Most ingested foreign bodies (80–90%) pass spontaneously [1,2]. McKechnie et al reported the first foreign body removal using a flexible endoscope in 1972 [3]. Since then, approximately 10–20% of foreign bodies require an endoscopic procedure for removal and <1% require surgery [1]. Although endoscopic treatment is minimally invasive, certain complications should not be ignored, such as laceration, bleeding, and perforation.

The reported complication rate in some studies was as high as 50% [4–7] and the major complication rate was about 7.3–25.8% [4,5,7–9]: laceration 9.1–16% [4,6,7,9]), perforation 1.5–8.1% [4–7,9]), and hemorrhage 3.4–5.0% [6,9]). The most frequently reported risk factors for complication were time interval between ingestion and endoscopic management, and the sharpness of the foreign body [7,10]. The rate of perforation caused by ingested sharp-pointed objects was 35% [11]. Therefore, efforts should be directed toward further reducing complication rates. Application of protective equipment, such as overtubes, protector hoods, and transparent caps, have already reduced the rate of mucosal injury during foreign body removal [12].

In addition, decision-making about the timing of an endoscopic intervention is still a problem, especially in the emergency setting. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommended emergent endoscopic procedure within 6 hours for esophageal obstruction or sharp-pointed objects in the esophagus and urgent within 24 hours for other foreign bodies [1]. In fact, there are limited reports on the application of these recommendations in the management of ingested foreign bodies and food bolus in adults. Furthermore, supporting evidence from China is lacking. Therefore, this retrospective study evaluated the 10-year experience of a single hospital in China with emergency removal of ingested foreign bodies in 586 adults.

Material and Methods

DATA COLLECTION:

Patient demographic data that were analyzed included age, sex, accidental vs intentional ingestion, and symptoms at admission. Clinical features of foreign bodies included type, size, sharpness, number, and location. We sorted the ingested foreign bodies into 4 groups according to their nature: sharp-pointed objects (eg, jujube [also referred to as red date] pits, poultry bones, fish bones), long objects (≥6 cm) (eg, pens, chopsticks), blunt objects (eg, plastic fragment), and food bolus, according to ESGE recommendations [1]. Endoscopic data that were analyzed included impaction time, endoscopic methods, accessory devices, associated GI tract diseases, and complications during the procedure.

TIMING OF ENDOSCOPIC REMOVAL:

The 2016 ESGE guideline recommends emergent (preferably within 2 hours, but at the latest within 6 hours) therapeutic esophagogastroduodenoscopy to remove foreign bodies that obstruct the esophagus and for sharp objects or corrosive batteries that may perforate the esophagus. The guideline also recommends urgent (within 24 hours) therapeutic esophagogastroduodenoscopy for other esophageal foreign bodies without complete obstruction (recommendation 7). For foreign bodies in the stomach, ESGE recommends urgent (within 24 hours) therapeutic esophagogastroduodenoscopy for sharp-pointed objects, magnets, batteries, and large/long objects. ESGE also recommends nonurgent (within 72 hours) therapeutic esophagogastroduodenoscopy for medium-sized blunt foreign bodies in the stomach (recommendation 10).

In our institution, endoscopy was performed as early as possible in all cases according to the ESGE guideline, and the timing of endoscopic intervention was classified into 3 types: emergent within 6 hours, urgent within 24 hours, and nonurgent within 72 hours [1]. Emergent intervention is required for patients with high-grade esophageal obstruction and ingestion of disk batteries or long sharp-pointed objects. Urgent intervention is required for esophageal foreign objects that are not sharp-pointed, food impaction without complete obstruction, sharp-pointed objects in the stomach or duodenum, objects longer than 6 cm in length, and magnets within endoscopic reach.

ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES:

All patients gave informed consent for the procedure. Before endoscopy, plain radiographs were routinely performed in the initial investigation. Each patient underwent an upper endoscopy under local pharyngeal anesthesia. Intravenous sedation (usually propofol plus fentanyl) was employed if there were no contraindications; however, it might not have always been available during an emergency. Standard endoscopic video systems (EVIS LUCERA CV-260/CLV-260 and EVIS LUCERA ELITE CV-290/CLV-290SL; Olympus Medical System) were used for the removal of foreign bodies. Accessories used for foreign body removal were biopsy forceps, foreign body forceps, retrieval nets, snares, and retrieval baskets. For sharp foreign bodies, we used a transparent distal hood to store the foreign bodies to avoid mucosal injury [12]. Procedure success was considered as complete removal from the digestive tract, with subsequent confirmation of absence of foreign bodies on assessment of the digestive tract.

COMPLICATIONS:

After removal, diagnostic endoscopy was performed to determine the procedure-induced complications, such as minor mucosal injuries (abrasions or small erosions), deep laceration, perforation, or bleeding that required additional procedures to achieve hemostasis. Symptoms indicating perforation include fever, tachycardia, peritonitis, subcutaneous crepitus, and swelling of the neck or chest. Computed tomography (CT) is indicated if perforation is suspected based on the clinical or radiological findings. Surgical treatment was considered in cases of complications that could not be resolved endoscopically (eg, bleeding) or after unsuccessful attempts.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Continuous variables were expressed as medians and ranges and were compared using the independent sample

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS:

A total of 586 out of 642 screened patients were included. A slight female predominance was noticed (55.3%) and the median (range) age was 57 (17–100) years. The most frequent presentation was a history of foreign body ingestion without any associated manifestations (n=251, 42.8%). Dysphagia and a sense of a lump behind the sternum was the second common category (n=222, 37.9%), followed by chest pain (n=71, 12.1%), and others (n=42, 7.2%). Diagnosis of foreign body trapping was made using patient history, and witnesses of foreign body ingestion in most cases. A total of 16 patients (2.5%) had underlying gastrointestinal diseases. Esophageal stricture due to the previous corrosive injury was the most common pathology (n=11, 68.8%), followed by esophageal carcinoma/malignancy (n=4, 25.0%), and duodenum carcinoma (n=1, 6.3%).

CHARACTERISTICS AND LOCATION OF FOREIGN BODIES:

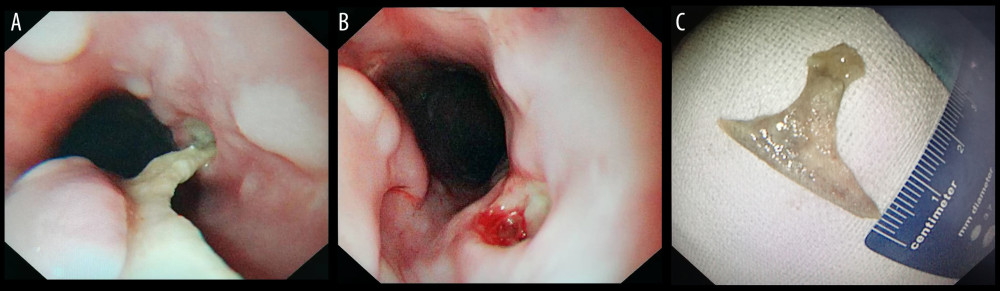

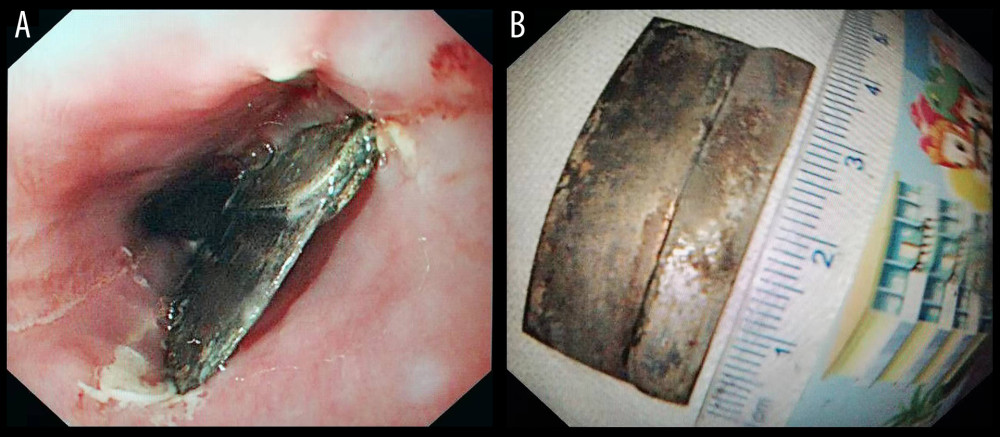

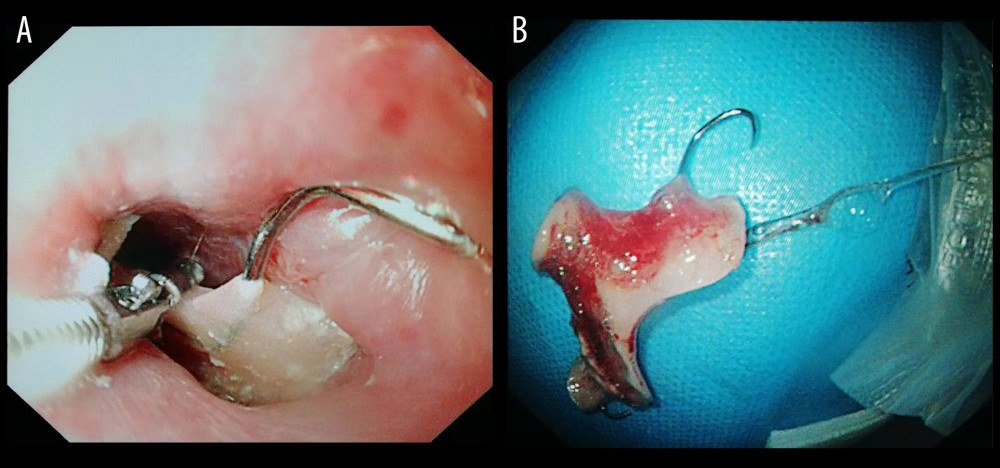

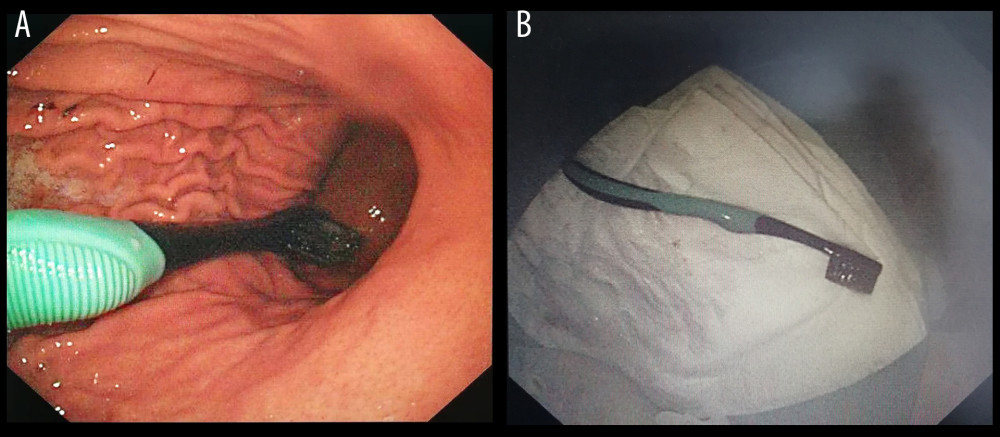

Foreign body ingestion was incidental in 95% of cases; mostly food-related (n=488, 83.3%) and rarely non-alimentary (n=53, 9.0%). Foreign body ingestion sometimes occurs in psychiatric patients (n=10), drug abusers (n=6), and in prisoners (n=4). The major types of foreign bodies were jujube or red date pits (n=394, 67.2%), followed by poultry bones (n=54, 9.2%), food boluses (n =20; 3.4%), fish bones (n=20, 3.4%), and dentures (n=13; 2.2%). Other types of foreign bodies included metallic foreign bodies, medication foil, pens, lighter, chopsticks, toothbrush, and plastic fragment (Figures 1A–1C, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4A, 4B, 5A, 5B, 6A, 6B). Ten patients had 2 or more foreign bodies (Table 1).

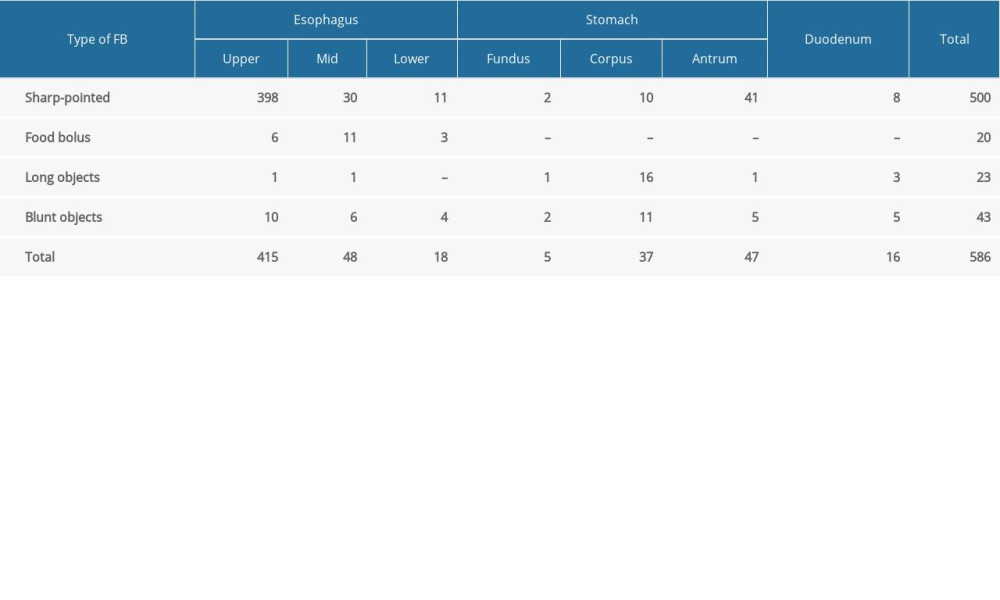

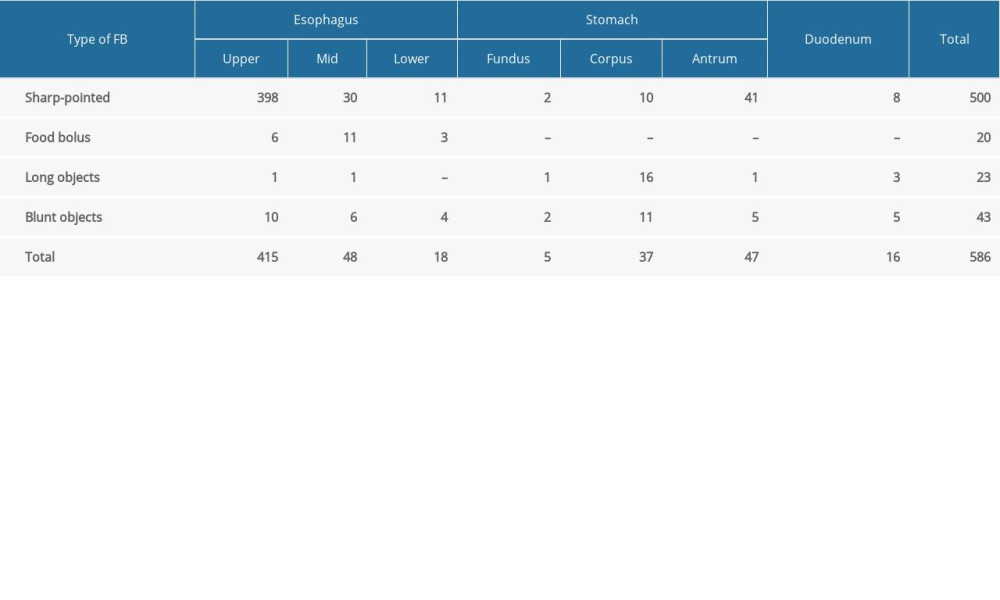

The median (range) diameter was 2.5 (1–24) cm: 2.5 (1.5–4.0) cm for sharp ones and 16.9 (10–24) cm for long ones. The most common site of foreign body lodgment was the esophagus (n=481; 82.1%), with the upper esophagus (n=415; 70.8%) being the predominant site (Figures 1A–1C, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B). Other lodgment sites were the stomach (n=89, 15.2%) and duodenum (n=16; 2.7%) (Figures 4A, 4B, 5A, 5B, 6A, 6B). There was a significant correlation between the type of foreign body and its location; 439 (87.8%) sharp-pointed foreign bodies were located in the esophagus, while 18 (78.3%) long foreign bodies were located in the stomach (Table 2).

TIMING AND DEVICES:

The time interval between ingestion and endoscopic examination could not be found in 34 patients. Among the remaining 552 patients, 45.6% (n=252) received emergent removal within 6 hours, while 32.2% (n=178) underwent urgent within 24 hours. The remaining 122 patients were referred from other centers and the time intervals were longer than 24 hours. Frequently-used devices for retrieval were retrieval forceps (n=529, 90.3%), snares (n=31, 5.3%), biopsy forceps (n=12, 2.0%), and endoscopic baskets (n=3, 0.5%). The remaining 10 patients used retrieval forceps and snares together. Snares were the most commonly used device for long foreign bodies (64.3%), while retrieval forceps were used most commonly for the remaining types (94.5%).

SUCCESS AND TECHNICAL COMPLICATIONS:

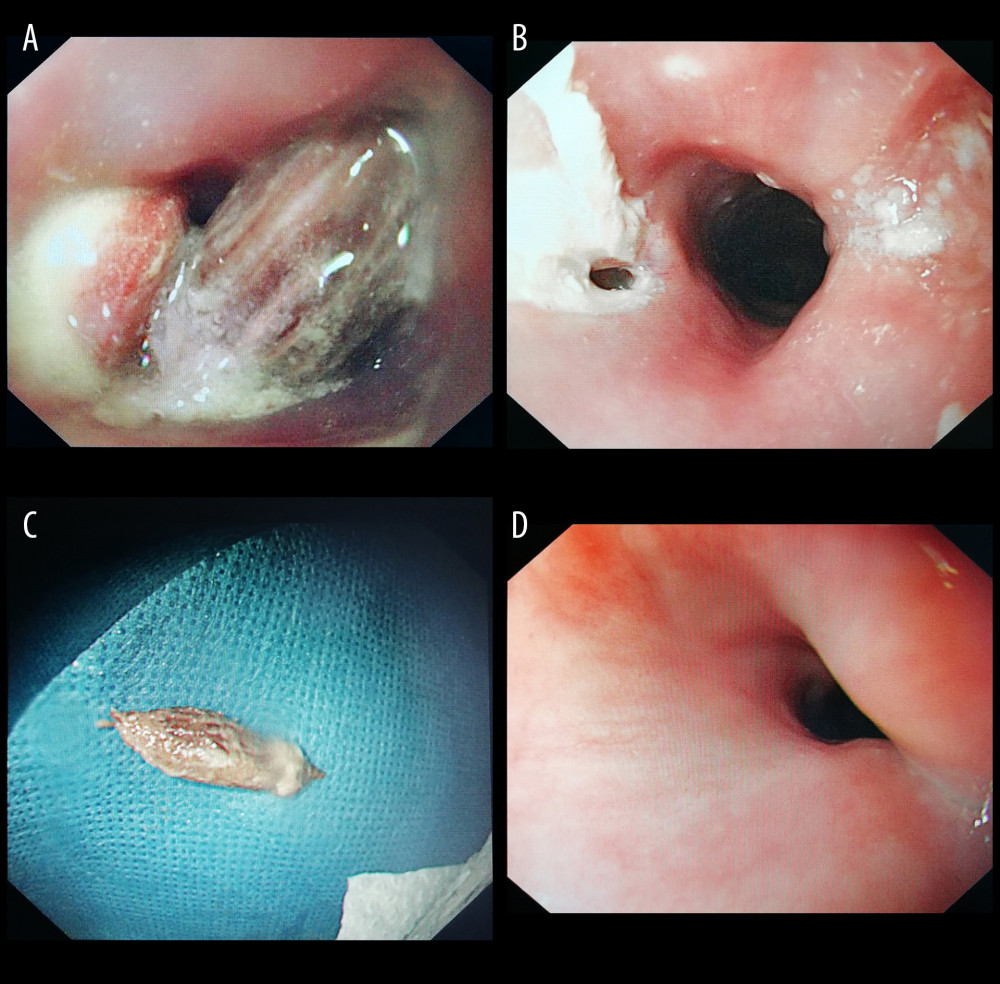

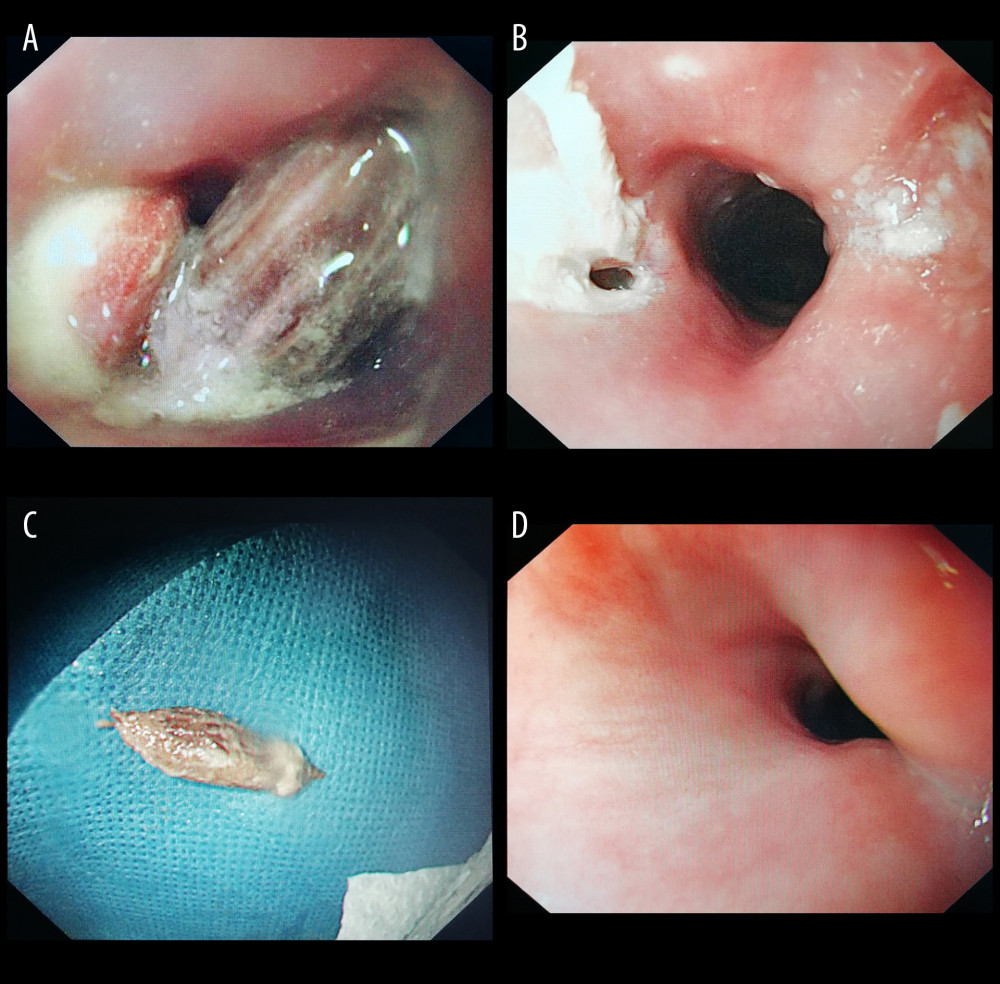

There were 583 (99.5%) successfully removed foreign bodies, and 3 removal attempts failed (2 dentures and 1 poultry bone). Complications were found in 105 patients (17.9%), including mucosal abrasion or erosion (n=60, 10.2%), laceration (n=8, 1.4%), deep ulceration (n=17, 2.9%), and perforation (n=20, 3.4%). Major complications, such as laceration, deep ulceration, and perforation, occurred in 45 patients (7.7%) (Figure 7A–7D). Among these 45 patients, 4 perforations needed surgery and the remaining patients were treated medically.

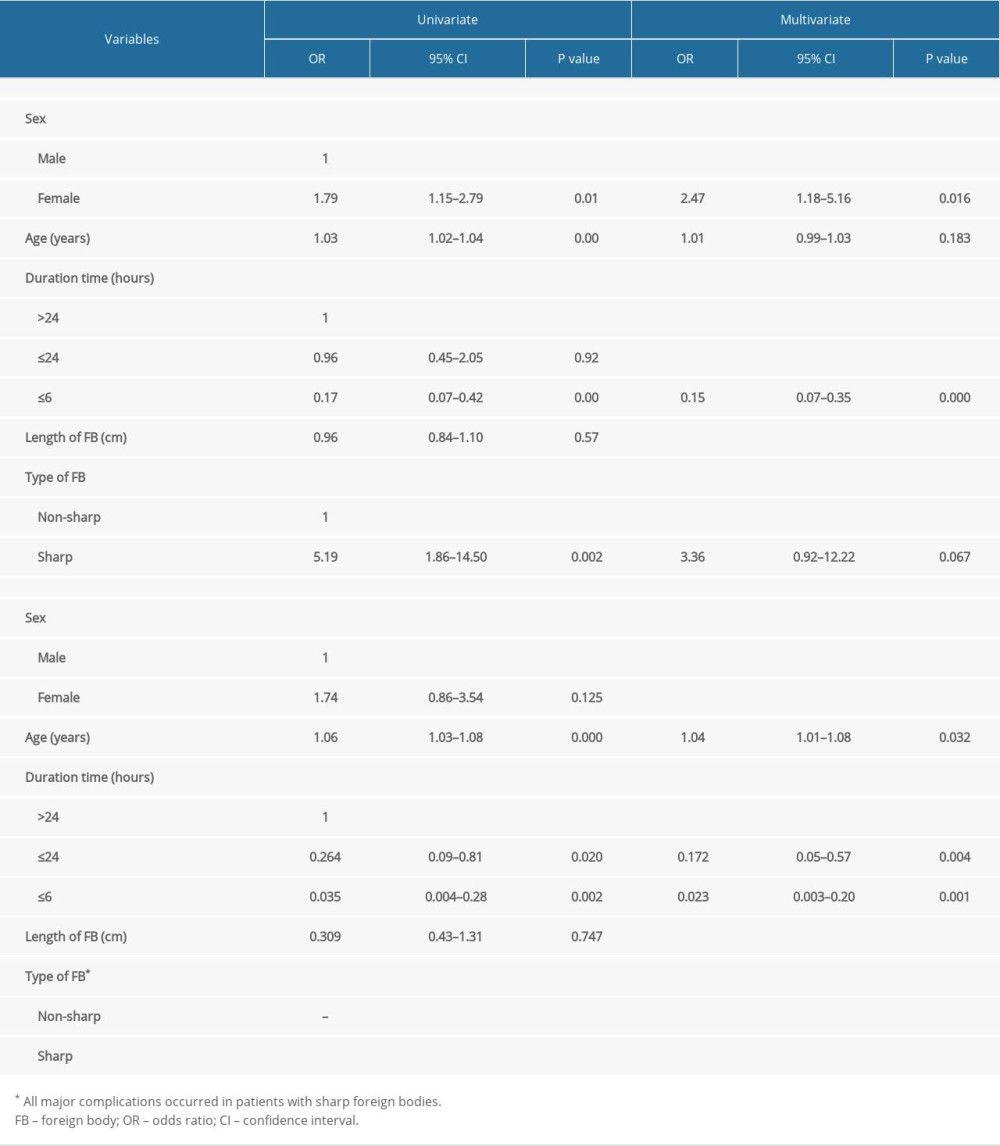

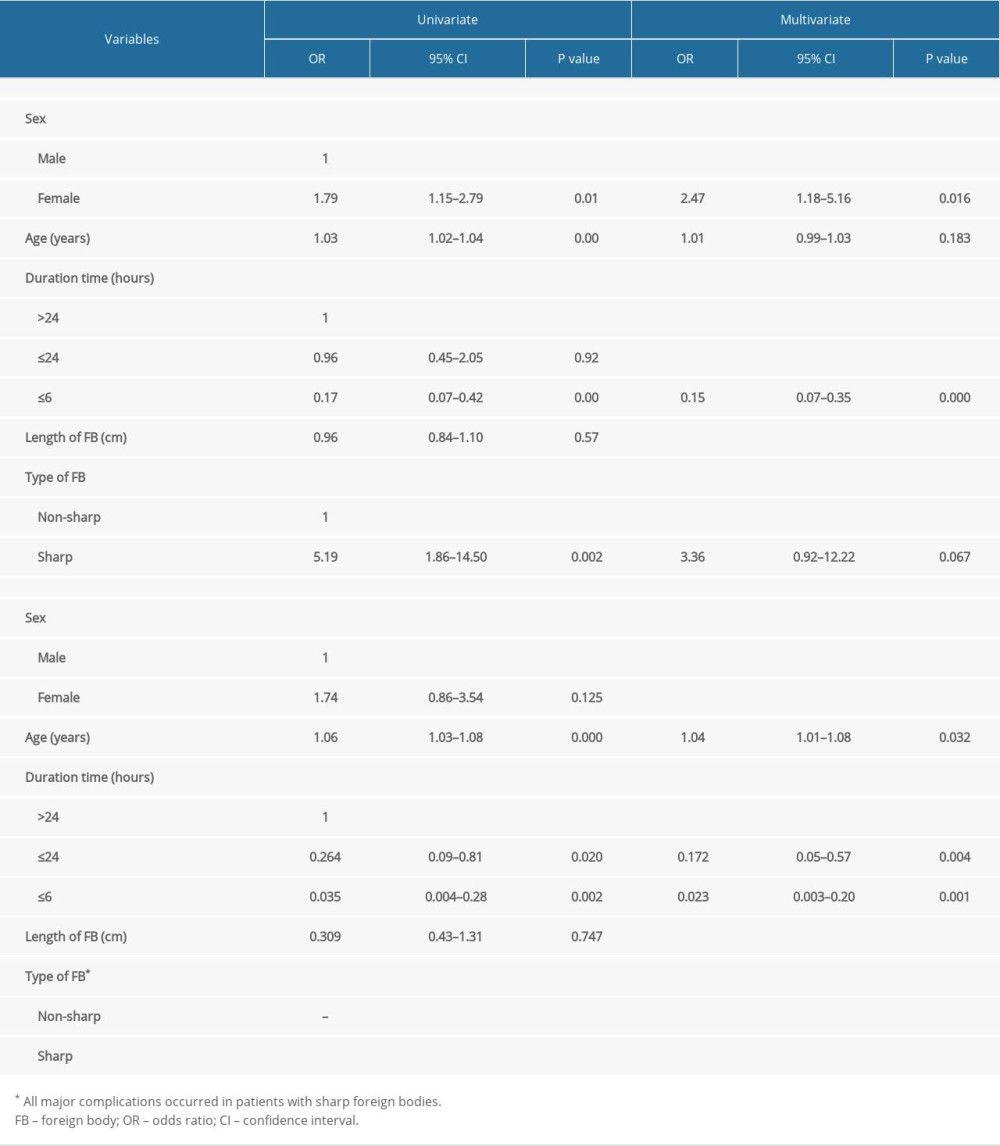

For all complications, female sex, older age, non-emergent endoscopy, and sharper objects were associated with higher complications in univariate analysis. Female sex and non-emergent endoscopy were significantly associated with higher complication rates according to multivariate analysis (Table 3). For major complications, older age, time interval >24 hours, and sharper objects were associated with major complications in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Notably, all major complications occurred in patients who ingested sharp objects. When adjusted for cofounding factors, the odds ratios (95% CI) were 0.02 (0.003–0.20) for emergent endoscopy and 0.17 (0.05–0.57) for urgent endoscopy, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, sharp-pointed objects, such as jujube or red date pit, were the most common foreign bodies, and the upper esophagus was the most common site of foreign body lodgment in adults. The management of foreign bodies in our series corresponded closely to the 2016 ESGE guideline recommendations for foreign body ingestion. The removal success rate was nearly 100%. The rate of any complication during removal was 17.9% and that of major complications was 7.7%. We demonstrated that emergent endoscopy with 6 hours could reduce the risk of overall complications.

Foreign body types are correlated with geographical and cultural differences in dietary habits. The most common foreign body in adults is food bolus in Western countries [13]. However, in Asian countries, sharp objects, including fish bones, chicken bones, fruit pits, and dentures are the most commonly ingested objects [4,7,14–16]. Fish bones are the most common foreign body in South China, while jujube pit is most common in northwest China [10,14–16]. Jujube is a dark red plumlike fruit of Old-World buckthorn trees, and jujube pits usually have 2 sharp points that can penetrate the wall of the GI tract (Figure 7A–7C) [10]. Our observation on jujube pits ingestion may be because of the high consumption of jujube in northwest China.

Our findings about long foreign bodies and food bolus were consistent with previous studies. Long foreign bodies occur more commonly in people with psychiatric disorders, alcohol intoxication, and in incarcerated individuals looking for an opportunity to be sent to a medical facility. Generally, objects longer than 5–6 cm will not pass through the duodenal sweep, and most long foreign bodies were lodged in the stomach. Food bolus impaction was often combined with an underlying structural abnormality such as esophageal web, esophageal rings, or a benign or malignant esophageal stricture.

About 10–20% of foreign bodies cannot pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously, and flexible endoscopy is the mainstay of foreign body removal [16–18]. In the last 10 years, the reported success rate of removal has gradually increased to 93–100% [7,9,18–21] due to improved equipment greater expertise. However, the high rate of technical success did not translate into lower rates of complications. The complication rate has been reported to range from 0.5% to 50.0%, depending on what is considered as a complication (such as mucosal erosions in some series) [4–7,9,20–24]. Together with our study (success rate of 99.5% and complication rate of 18%), these paradoxical findings suggested that the high complication rate does not result from technical issues. Whether the sharpness of the foreign body is a risk factor for complications has been controversial. Sharp foreign bodies were identified as risk factors for complications in multiple studies [4,7,24]. When adjusted for other risk factors, sharp-pointed objects were not associated with a higher overall complication rate, but were associated with a higher rate of major complications in the present study.

It is well recognized that complication rates increase with impaction time; however, few studies have explored the relationship between time interval between ingestion and endoscopic management and outcomes. The reported time intervals included 24 hours [8,24–26], 15 hours [27], 12 hours [7], and 6 hours [23]. The ESGE recommends emergent endoscopy within 6 hours and urgent endoscopy within 24 hours for different kinds of objects. No previous study has evaluated the effectiveness of these recommendations. Our study demonstrated that time interval within 6 hours could reduce all complications, including major ones. Time interval between 6 and 24 hours could reduce major complications, but not overall complications. This may be explained by the wide use of safety measures, such as overtubes and transparent caps [12], which can widen the therapeutic window and reduce major complications. Despite protective devices, mild complications were inevitable, and time is the true element of success.

The present study has some limitations. The study involved a retrospective analysis, data on some minor complications were not available, and the degree of mucosal damage was not objectively evaluated in all cases, so some potential bias might have been added. However, due to the relatively large numbers of cases with major complications, it was possible to investigate the risk factors. Second, psychiatric disease is a risk factor for foreign body lodgment, but the numbers were relatively small, and we did not analyze it. Finally, most foreign bodies were sharp-pointed objects in the present study, and caution should be used when extrapolating the results to other conditions.

Conclusions

Flexible endoscopy is the mainstay of foreign body removal, with a success rate near 100%. The ESGE recommendations could significantly reduce the complication rates for adults in the emergency setting. Longer impaction time, older age, and sharp-pointed objects were predictive factors for complications, especially major complications. The findings from this retrospective study supported the ESGE recommendations that endoscopic removal of ingested foreign bodies from the upper GI tract within 6 hours is needed to reduce complication rates for adults in the emergency setting. Further studies comparing patients with different dietary habits are needed.

Figures

Figure 1. Sharp-pointed object (poultry bone) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Poultry bone in the esophagus; (B) Esophageal ulcers after removal; (C) Removed poultry bone. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

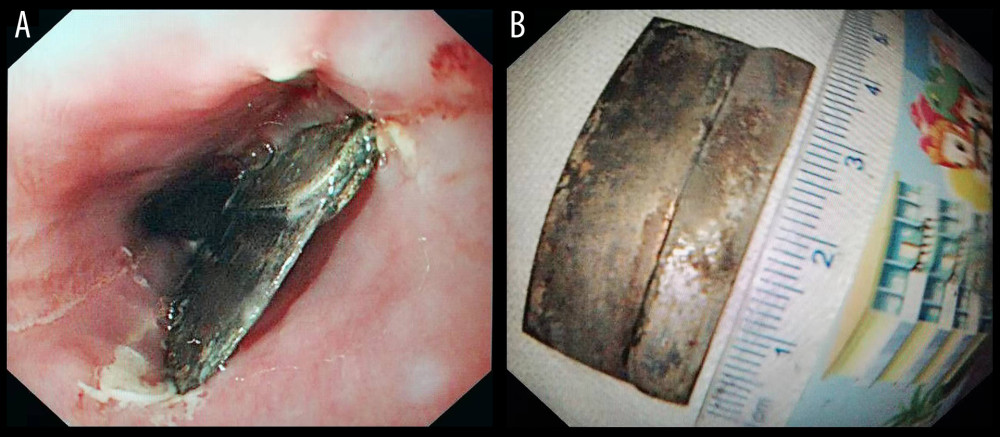

Figure 1. Sharp-pointed object (poultry bone) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Poultry bone in the esophagus; (B) Esophageal ulcers after removal; (C) Removed poultry bone. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 2. Sharp-pointed object (single-edge razor blade) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Single-edge blade in the esophagus; (B) Removed single-edge blade. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

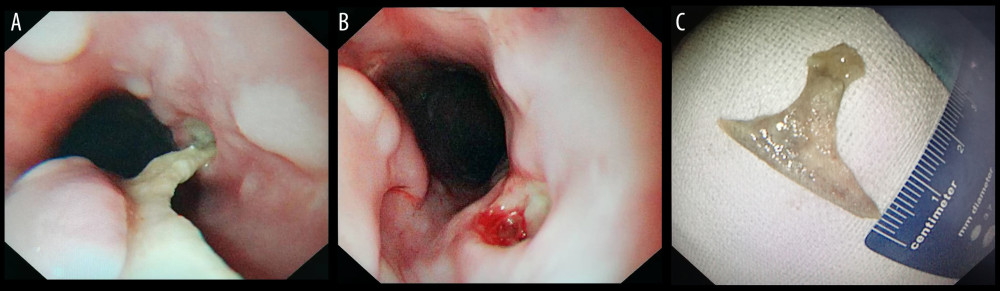

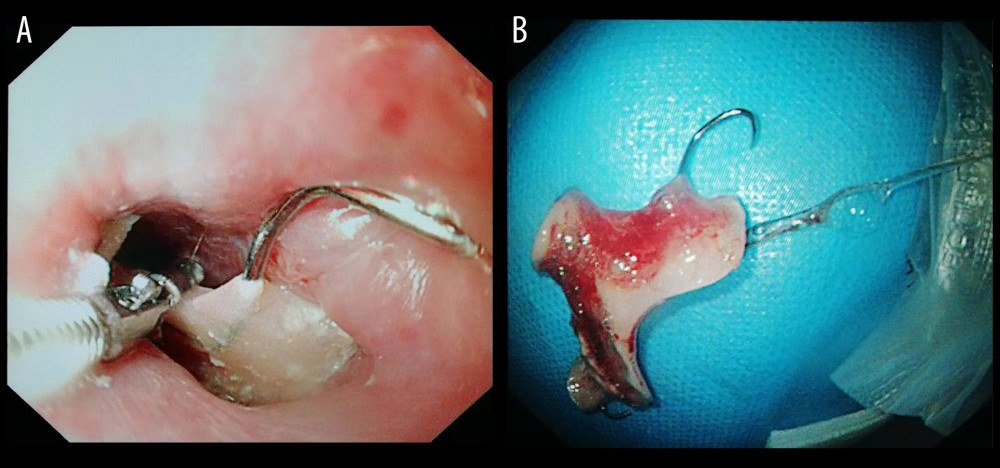

Figure 2. Sharp-pointed object (single-edge razor blade) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Single-edge blade in the esophagus; (B) Removed single-edge blade. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 3. Sharp-pointed object (denture) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Denture in the esophagus; (B) Removed denture. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

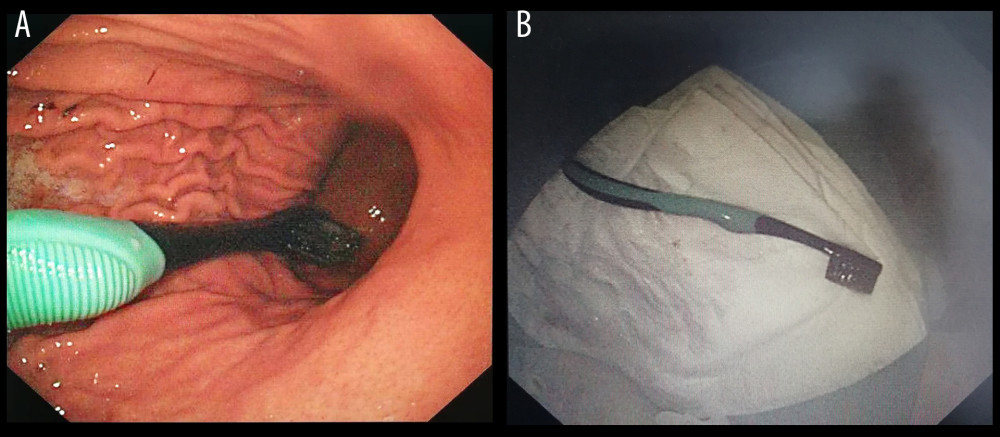

Figure 3. Sharp-pointed object (denture) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Denture in the esophagus; (B) Removed denture. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 4. Long object (toothbrush) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Toothbrush in the stomach; (B) Removed toothbrush. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

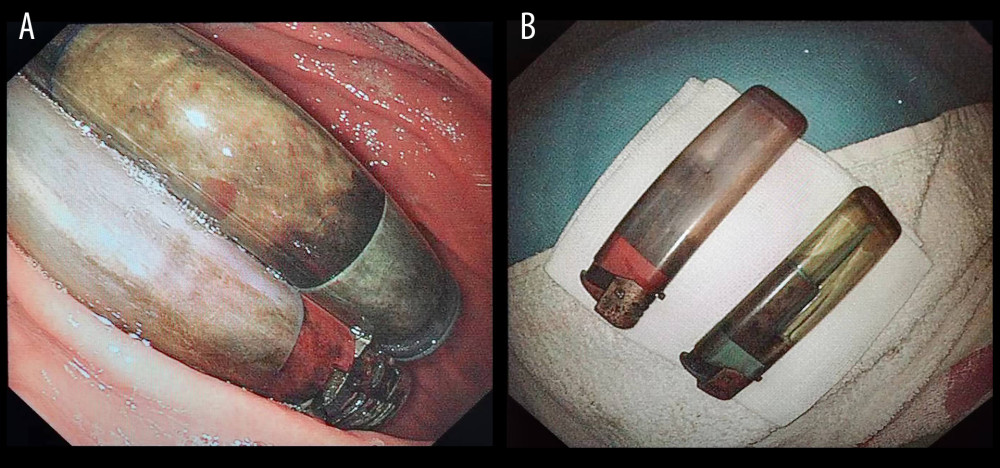

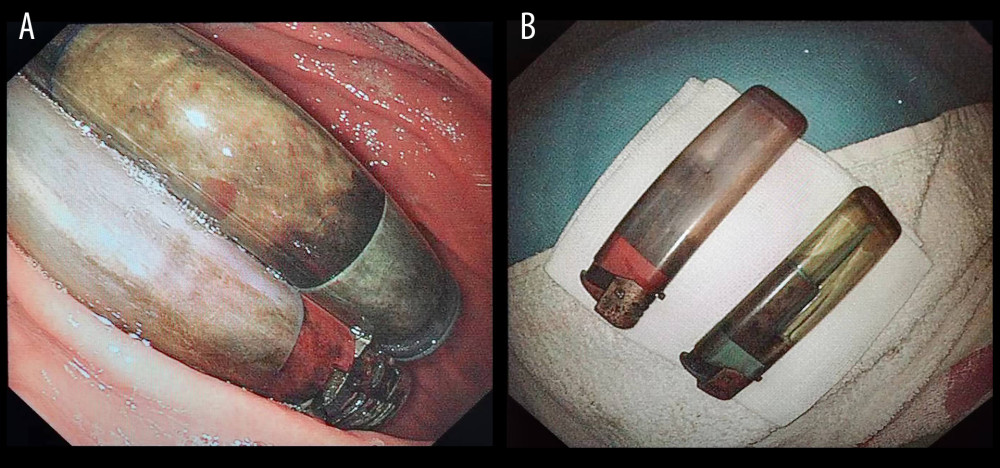

Figure 4. Long object (toothbrush) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Toothbrush in the stomach; (B) Removed toothbrush. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 5. Long objects (lighters) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Lighters in the stomach; (B) Removed lighters. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

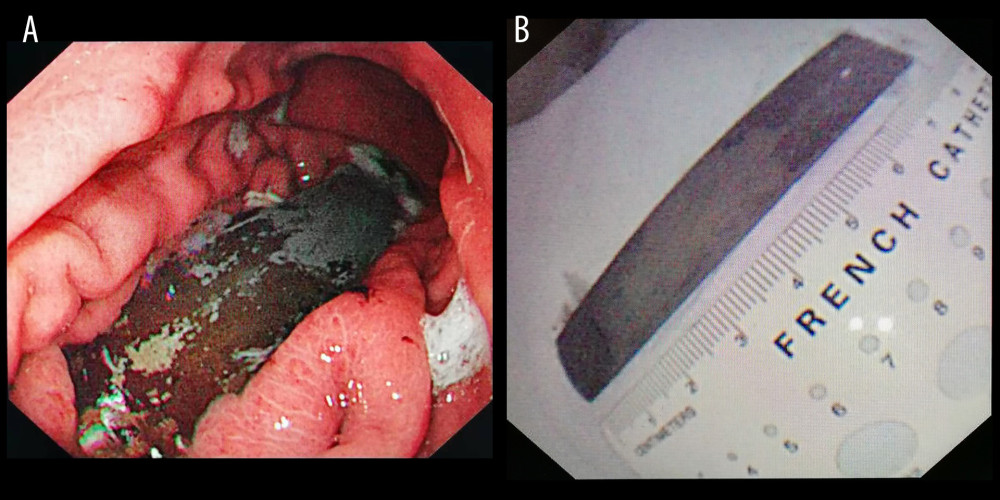

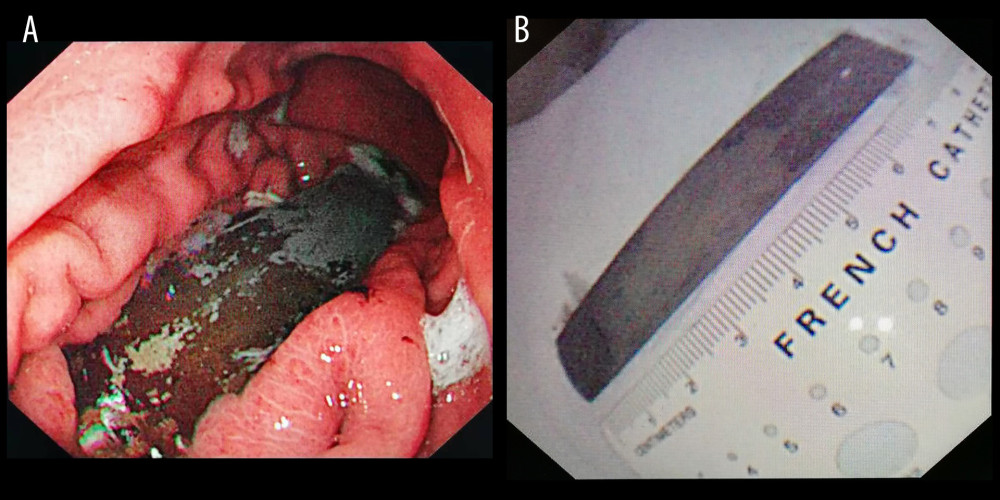

Figure 5. Long objects (lighters) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Lighters in the stomach; (B) Removed lighters. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 6. Long object (steel plate) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Steel plate in the stomach; (B) Removed steel plate. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 6. Long object (steel plate) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Steel plate in the stomach; (B) Removed steel plate. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).  Figure 7. Jujube pit ingestion with perforation before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Jujube pit in the esophagus; (B) Perforation after removal; (C) Removed jujube pit; (D) Healed perforation during follow-up. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 7. Jujube pit ingestion with perforation before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Jujube pit in the esophagus; (B) Perforation after removal; (C) Removed jujube pit; (D) Healed perforation during follow-up. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). References

1. Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline: Endoscopy, 2016; 48(5); 489-96

2. Lin JH, Fang J, Wang D, Chinese expert consensus on the endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract (2015, Shanghai, China): J Dig Dis, 2016; 17(2); 65-78

3. McKechnie JC, Gastroscopic removal of a phytobezoar: Gastroenterology, 1972; 62(5); 1047-51

4. Sung SH, Jeon SW, Son HS, Factors predictive of risk for complications in patients with oesophageal foreign bodies: Dig Liver Dis, 2011; 43(8); 632-35

5. Zhang X, Jiang Y, Fu T, Esophageal foreign bodies in adults with different durations of time from ingestion to effective treatment: J Int Med Res, 2017; 45(4); 1386-93

6. Lee HJ, Kim HS, Jeon J, Endoscopic foreign body removal in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Risk factors predicting conversion to surgery: Surg Endosc, 2016; 30(1); 106-13

7. Hong KH, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Risk factors for complications associated with upper gastrointestinal foreign bodies: World J Gastroenterol, 2015; 21(26); 8125-31

8. Loh KS, Tan LK, Smith JD, Complications of foreign bodies in the esophagus: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2000; 123(5); 613-16

9. Yuan J, Ma M, Guo Y, Delayed endoscopic removal of sharp foreign body in the esophagus increased clinical complications: An experience from multiple centers in China: Medicine, 2019; 98(26); e16146

10. Song JT, Chang XH, Liu SS, Individualized endoscopic management strategy for impacting jujube pits in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A 3-year single-center experience in northern China: BMC Surg, 2021; 21(1); 18

11. Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies: Gastrointest Endosc, 2002; 55(7); 802-6

12. Zhang S, Wang J, Wang J, Transparent cap-assisted endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper esophagus: A randomized, controlled trial: J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013; 28(8); 1339-42

13. Mosca S, Manes G, Martino R, Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Report on a series of 414 adult patients: Endoscopy, 2001; 33(8); 692-96

14. Zhang S, Cui Y, Gong X, Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in South China: A retrospective study of 561 cases: Dig Dis Sci, 2010; 55(5); 1305-12

15. Lai AT, Chow TL, Lee DT, Kwok SP, Risk factors predicting the development of complications after foreign body ingestion: Br J Surg, 2003; 90(12); 1531-35

16. Tseng CC, Hsiao TY, Hsu WC, Comparison of rigid and flexible endoscopy for removing esophageal foreign bodies in an emergency: J Formos Med Assoc, 2016; 115(8); 639-44

17. Ambe P, Weber SA, Schauer M, Knoefel WT, Swallowed foreign bodies in adults: Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2012; 109(50); 869-75

18. Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MAASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions: Gastrointest Endosc, 2011; 73(6); 1085-91

19. Emara MH, Darwiesh EM, Refaey MM, Galal SM, Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies from the upper gastrointestinal tract: 5-year experience: Clin Exp Gastroenterol, 2014; 7; 249-53

20. Limpias Kamiya KJ, Hosoe N, Takabayashi K, Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies: A retrospective study in Japan: World J Gastrointest Endosc, 2020; 12(1); 33-41

21. Yao CC, Wu IT, Lu LS, Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract of adults: Biomed Res Int, 2015; 2015; 658602

22. Skok P, Skok K, Urgent endoscopy in patients with “true foreign bodies” in the upper gastrointestinal tract – a retrospective study of the period 1994–2018: Z Gastroenterol, 2020; 58(3); 217-23

23. Lee CY, Kao BZ, Wu CS, Retrospective analysis of endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract of adults: J Chin Med Assoc, 2019; 82(2); 105-9

24. Geng C, Li X, Luo R, Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A retrospective study of 1294 cases: Scand J Gastroenterol, 2017; 52(11); 1286-91

25. Wu WT, Chiu CT, Kuo CJ, Endoscopic management of suspected esophageal foreign body in adults: Dis Esophagus, 2011; 24(3); 131-37

26. Palta R, Sahota A, Bemarki A, Foreign-body ingestion: characteristics and outcomes in a lower socioeconomic population with predominantly intentional ingestion: Gastrointest Endosc, 2009; 69(3 Pt 1); 426-33

27. Feng S, Peng H, Xie H, Management of sharp-pointed esophageal foreign-body impaction with rigid endoscopy: A retrospective study of 130 adult patients: Ear Nose Throat J, 2020; 99(4); 251-58

Figures

Figure 1. Sharp-pointed object (poultry bone) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Poultry bone in the esophagus; (B) Esophageal ulcers after removal; (C) Removed poultry bone. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 1. Sharp-pointed object (poultry bone) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Poultry bone in the esophagus; (B) Esophageal ulcers after removal; (C) Removed poultry bone. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 2. Sharp-pointed object (single-edge razor blade) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Single-edge blade in the esophagus; (B) Removed single-edge blade. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 2. Sharp-pointed object (single-edge razor blade) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Single-edge blade in the esophagus; (B) Removed single-edge blade. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 3. Sharp-pointed object (denture) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Denture in the esophagus; (B) Removed denture. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 3. Sharp-pointed object (denture) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Denture in the esophagus; (B) Removed denture. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 4. Long object (toothbrush) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Toothbrush in the stomach; (B) Removed toothbrush. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 4. Long object (toothbrush) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Toothbrush in the stomach; (B) Removed toothbrush. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 5. Long objects (lighters) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Lighters in the stomach; (B) Removed lighters. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 5. Long objects (lighters) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Lighters in the stomach; (B) Removed lighters. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 6. Long object (steel plate) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Steel plate in the stomach; (B) Removed steel plate. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 6. Long object (steel plate) before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Steel plate in the stomach; (B) Removed steel plate. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Figure 7. Jujube pit ingestion with perforation before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Jujube pit in the esophagus; (B) Perforation after removal; (C) Removed jujube pit; (D) Healed perforation during follow-up. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Figure 7. Jujube pit ingestion with perforation before and after endoscopic removal. (A) Jujube pit in the esophagus; (B) Perforation after removal; (C) Removed jujube pit; (D) Healed perforation during follow-up. Endoscopic images were recorded during procedures and edited via Microsoft PowerPoint (version 2016, Microsoft, USA). Tables

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 586 included patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 586 included patients. Table 2. Sites of foreign body lodgment according to foreign body (FB) type.

Table 2. Sites of foreign body lodgment according to foreign body (FB) type. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall complications and major complications.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall complications and major complications. Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 586 included patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 586 included patients. Table 2. Sites of foreign body lodgment according to foreign body (FB) type.

Table 2. Sites of foreign body lodgment according to foreign body (FB) type. Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall complications and major complications.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall complications and major complications. In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variation of Medical Comorbidities in Oral Surgery Patients: A Retrospective Study at Jazan ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943884

08 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Evaluation of Foot Structure in Preschool Children Based on Body MassMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943765

15 Apr 2024 : Laboratory Research

The Role of Copper-Induced M2 Macrophage Polarization in Protecting Cartilage Matrix in OsteoarthritisMed Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943738

07 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 179 Male Third- and Fourt...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943468

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952